I have a new appreciation for the power of a story in the heart of a human.

As I stand here at the ‘turning of the years’ and look toward another year to come I find that “The color of the world, Is changing day by day…” On the one hand I can see the black bleakness of a people and culture who have abandoned truth, beauty, and goodness. We have embraced, instead, the lies of relativism and “self realization,” a misguided quest for equity, and the consuming of all around us to feed ever growing hungers on all levels (physical, spiritual, and emotional). Yet on the other hand, in the fading light of this day I can yet see the “red [of a] world about to dawn.”

In recent posts[i] Darrow Miller has well described the cultural corner we have turned. From a society rooted in a Biblical paradigm we have become a post-Christian, post-modern (dare I say even post post-modern?), relativist, self-indulgent people. We have traded the true concept of time—that which finds meaning in the hope of timeless eternity—for an endless, detached series of “now” events without connection to a past or a future. We recognize the decayed roots and rotten fruit of the choices of our chosen leaders, and our apparent inability to stem the tide. This is the dark night falling around us. But the red dawn of a new day faintly glows.

Where do I see this hope? From my recent second viewing of the current cinematic release of Victor Hugo’s Les Miserables (the source of the quotes above). And once again, my heart is stirred that there is yet something in the human soul that cries out for a better day, that a better way lies ahead, still to be discovered. This story never ceases to move me. Let me share the hope I see.

The story is primarily aimed at the West, and my response has in view mostly the US and the church in the West. Yet the themes are timeless and borderless. For those unfamiliar with the narrative, here is a very brief synopsis.

Hugo wrote in 1862 to examine the oppression and abject condition of the poor in France in the mid-nineteenth century. Despite revolutions and attempts to create a just and equal society based on principles of the Enlightenment, nothing had changed. The poor were becoming more wretched, the rich more affluent and insular (the condition of many places in the world today). “Examining the nature of law and grace, the novel elaborates upon the history of France, the architecture and urban design of Paris, politics, moral philosophy, antimonarchism, justice, religion, and the types and nature of romantic and familial love.”[ii]

The story follows four main characters, the convergence of their lives and the consequences of their ideas and actions. Jean Valjean is a paroled galley-slave convict who had served 19 years for stealing a loaf of bread for his nephew. He is offered redemption. He changes his identity, becoming wealthy and benevolent. Javert is a police inspector who started his career as a warden at the Toulon prison where Valjean was incarcerated. Throughout the story Javert is pursuing Valjean until the tragic climax, the moment when he is shown mercy by Valjean and cannot reconcile the demands of Law with the reality of grace. Thenardier is a thief-cum-corrupt innkeeper-cum-criminal boss. His is a story of descending depravity to feed his appetites. Fontine is a single mother, abandoned by her child’s father after using her for his pleasure. In desperation she places her child, Cossette, with Thenardier and his wife who mistreat the girl and extort the mother. Fontine resorts to prostitution to support her daughter, eventually losing everything including her health. At her death, Valjean (after escaping Javert) takes responsibility for Cossette and raises her as his own. The story culminates in the revolution of June 5/6, 1832 during which Cossette finds love with a student revolutionary, Marius. Valjean rescues Marius from death, justice overtakes the Thenardiers, and Javert comes to an untimely end.

I’m intrigued by the power of this story, and the meta-story behind it. On another level are the ideas and consequences illustrated by this story. Finally, there is the question of what in us the story is calling out to, what is the power of that call, and why the movie calls so strongly.

At the first level, this is the age-old story, in all its pain and glory, of the Prodigal Son. All the characters of the parable appear, either expressed or implied. In the Bishop of Digones we see the Father – extending the way to the light. In Jean Valjean (and to a lesser degree Fontine) we see the prodigal who loses his way, returns, and goes on to rescue others – the prodigal becomes the Father. Javert is the elder brother who cannot reconcile justice with mercy, law with grace. He will forever seek recompense and punishment rather than repentance and regeneration. In the Thenardiers we have the final end of the prodigal had he not turned – the utter end of those given to depravity. In short it is the story of the power of grace to bring about transformation from sin and shame, and the inability of law and human righteousness to do the same.

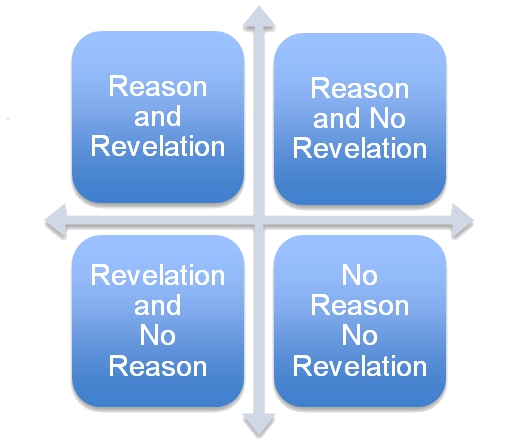

Yet this meta-story is but the peg on which hangs a deeper revelation. For in this story I also see illustrated in the lives of the characters the conflicts between the major worldviews of today and the consequences of those conflicts. Darrow Miller, in his teaching and writing, suggests that cultures and individuals approach truth in one of four ways.

Consider the graphic. The upper left quadrant represents the Biblical worldview, while socialism and old Iron Block Communism are seen in the upper right. The lower left captures the legalistic, dogmatic paradigms such as jihadism and Pharaseeism. Finally, the lower right quadrant corresponds to abject hedonistic animalism.

Consider the graphic. The upper left quadrant represents the Biblical worldview, while socialism and old Iron Block Communism are seen in the upper right. The lower left captures the legalistic, dogmatic paradigms such as jihadism and Pharaseeism. Finally, the lower right quadrant corresponds to abject hedonistic animalism.

Characters in Les Miserables fit into each of these. Jean Valjean, Fontine, Cosette, and to a degree Marius, live in Reason & Revelation. Valjean’s discovery of love instead of hate, of redemption over retribution, results in his consistent movement to righteous decisions and actions. Javert, on the other hand, lives in a world of the revelation of law alone. Certain actions demand certain reactions – no questions, no means of considering alternatives. Some of Marius’ fellow student revolutionaries (Enjoras, Combeferre, et al) seek answers and solutions by human reason alone. There is no higher truth to appeal to. We must make justice, equality, human dignity and right by our actions alone.

Finally, there is Thenardier, who lives in the abject wretchedness and depravity of no God, no good intent, no rationality – merely dog-eat-dog consumption. (This can be seen in a song from the theatrical production – “It’s a world where the dog eats the dog; Where they kill for bones in the street; And God in His Heaven; He don’t interfere; ‘Cause he’s dead as the stiffs at my feet; I raise my eyes to see the heavens; And only the moon looks down.”[iv]) Thenardier has been reduced to an animal existence. He knows no truth outside himself and his hungers, and no time other than now.

Francis Schaeffer, in his first three books – The God Who Is There, Escape from Reason, and He Is There And He Is Not Silent – develops the concept that we all have preconceptions of the nature of reality, preconceptions with natural consequences. Along the way those preconceptions come in conflict with reality. At that point we are challenged and become open to change. We move toward or away from truth (what Schaefer calls “true truth”). This is another way of looking at the above concept seen through the film. Hugo builds each character on a premise of reality, and each character follows that premise toward its end. Each faces the inevitable conflict, and either moves toward truth, or perishes.

However, these portrayals of truth, beauty and goodness, and their antitheses of lie, ugliness, depravity, do not explain the power of this movie to give hope. What is the power that compels in this performance?

That’s another question, for another post.

– Bob Evans

Bob Evans is Administrative Director of Global Network Ministries, Inc., and serves as secretary of the Board of Directors of Disciple Nations Alliance. He has travelled extensively in Asia and around the world serving local church movements and leading ministry and development teams from the U.S. Bob has four children and two grandchildren, and resides in Laguna Niguel, California.

[i] Has America Reached a Tipping Point?

The 2012 Election: Political Solutions Won’t Heal the Culture

One Geograpy, Two Nations: Why Is America Becoming More P0larized?

[ii] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Les_Miserables, http://a-fair-substitute-for-heaven.blogspot.com/2012/12/film-review-les-miserables.html

[iv] Les Miserables (Film & Musical) lyrics quoted or alluded to include:

What have I Done; Finale; Red & Black – ABC Café; Dog Eats Dog(Musical only); Javert’s Suicide; Stars.

2 Comments

Carlos Said Pires

February 14, 2013 - 11:41 amI’ve watched this movie. Very powerful message. I really appreciated this article.It is very interesting to see people’s reaction when law faces grace!

admin

February 14, 2013 - 12:01 pmHi, Carlos, thanks for reading and thanks for your comment.

Gary Brumbelow