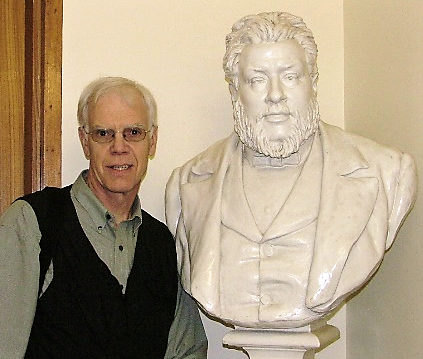

Charles Haddon Spurgeon (1834-1892)

Today’s evangelicalism derives from the fundamentalist movement, born around 1900 in reaction to liberal modernism, which had been influenced by Darwin’s new theory of naturalism. About the genesis of fundamentalism, Indian scholar Vishal Mangalwadi has noted,

In reacting against rationalism, Fundamentalism abandoned studying the books of God’s works and reason. The reformer’s slogan Sola Scriptura (Scriptures alone) began to be misunderstood to mean “Study only the Scriptures.” A theologian may learn Greek, but he does so to study the Bible, not Plato.

Over 100 years later, evangelicals still live with the fruit of this artificial separation between studying the Word of God and the world of God. Most evangelicals affirm the inerrancy and absolute authority of holy scripture. But many take that doctrine so far as to believe that God has spoken only through the Bible. It’s not unusual to hear someone appeal to 2 Peter 1:3 (“His divine power has granted to us all things that pertain to life and godliness”) to support that notion: “Everything you need to know is in the Bible.” But look again. Peter does not say “The Bible has granted to us all things …”

So we have an false dichotomy between the “sacred” and the “secular,” as if God has no interest in, ownership of, or authority over dirt and plants, ideas and books, people and careers. This contradiction comes in many flavors. Here’s one: You can either preach the true gospel, or you can preach the social gospel. You can have a ministry that is faithful to the scripture, or you can serve merely social concerns. You can address the spiritual needs of people, or their physical/social/emotional needs. But not both.

This unhappy and artificial sacred-secular divide has lingered in Western evangelicalism far too long. An understanding of why this divergence is unnecessary (as well as unbiblical) is way overdue. We have addressed it at this blog many times. (Go here for a list of articles, here for a flagship article.) This post is an attempt to help bridge that chasm by presenting the example of one well-known, widely admired preacher who combined an extraordinary pulpit ministry with a robust service to the social needs of his city.

I speak of the “prince of preachers,” Charles Haddon Spurgeon. As a preacher myself, I’m a big fan of Charles Spurgeon, if not a scholar of his life. But a brief survey of Lewis A. Drummond’s massive book, Spurgeon: Prince of Preachers (Kregel, 1992) suggests that this renowned Sunday pulpiteer practiced a Monday-Saturday life that exposes the sacred vs. secular myth for what it is.

I speak of the “prince of preachers,” Charles Haddon Spurgeon. As a preacher myself, I’m a big fan of Charles Spurgeon, if not a scholar of his life. But a brief survey of Lewis A. Drummond’s massive book, Spurgeon: Prince of Preachers (Kregel, 1992) suggests that this renowned Sunday pulpiteer practiced a Monday-Saturday life that exposes the sacred vs. secular myth for what it is.

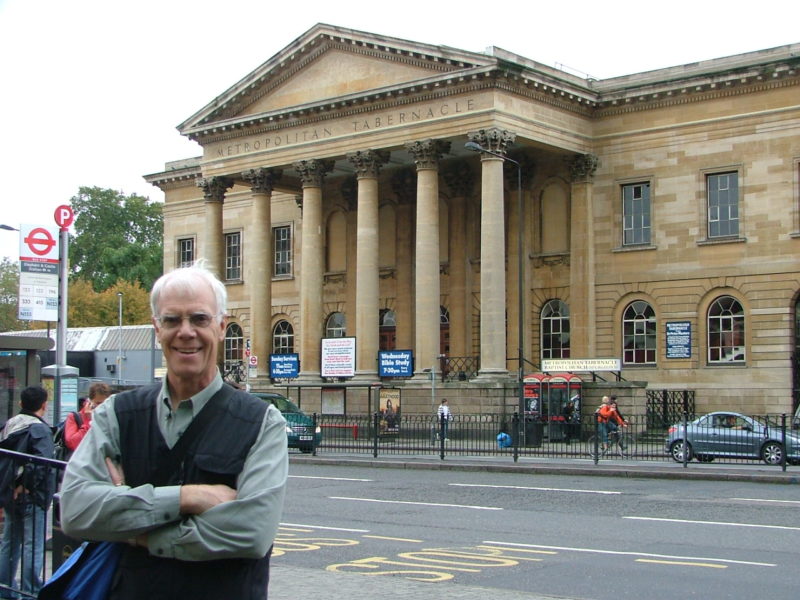

You can still visit the Metropolitan Tabernacle, Spurgeon’s famous church, though reduced in scope from its former glory. It’s directly across a very busy avenue from the Elephant and Castle shopping center. You’ll have to keep your wits about you to cross the street safely.

London’s streets looked different in the mid-nineteenth century when Spurgeon walked through their slums “to acquaint himself with the misery of these poor and destitute members of society.” Vast crowds came to hear him preach on Sunday, but during the week, Spurgeon decided to minister not “just to those who would come to him in need, he would reach out to touch the outcast as well. … for the poor and destitute of the Victorian society, ‘no one but the non-conformist minister was their friend.’” (401)

London’s streets looked different in the mid-nineteenth century when Spurgeon walked through their slums “to acquaint himself with the misery of these poor and destitute members of society.” Vast crowds came to hear him preach on Sunday, but during the week, Spurgeon decided to minister not “just to those who would come to him in need, he would reach out to touch the outcast as well. … for the poor and destitute of the Victorian society, ‘no one but the non-conformist minister was their friend.’” (401)

Spurgeon could always be moved by the desperate needs of Londoners. … The beautiful monuments and historic places of London like Trafalgar Square, Piccadilly, and the noble spires of Westminster Abbey, were a far cry from the ramshackled houses on the waterfront and the pubs and squalor. The average professional thief had hardly reached his teenage years. Young girls were drawn into prostitution at an alarming rate. (398)

Drummond speaks of Spurgeon’s wholistic ministry, something unusual for his time.

Almost unparalleled in church history, the ministry of Charles Haddon Spurgeon epitomized the perfect blending of evangelistic fervency and deep social concern. We have already investigated in some depth his utter commitment to leading people to faith in Christ. Perhaps the world shall never see a more effective pastor-evangelist than C.H. Spurgeon. But right beside that concern for people’s souls stood his commitment to fulfill people’s needs. He devoted much of his time and energy to that end. He will always stand as a symbol of a minister who developed his life of service in the beautiful balance of social ministries and evangelistic commitment. (398)

Spurgeon affirmed the primacy of the gospel, believing that “no social plans will make our earth a paradise while sin still curses it and Satan is abroad.” For Spurgeon, “seeing an individual come to faith in Christ and become a converted person still presented the best and basic means of revolutionising society.” (403)

Having said that, Spurgeon embraced the concept that “religion must be intended for this life; the duties of it cannot be practiced, unless they are practiced here … Christianity must be a practical down-to-earth religion that brought the teachings and ministry of Jesus right home to where the people lived.” (401)

Under his leadership, the Metropolitan Tabernacle operated a number of ministries to people of particular needs.

- The Stockwell Orphanage: “London in the mid-nineteenth century was every bit as tragic as Dicken’s description of the city in his novel, Oliver Twist.” (398)

- The Old Ladies’ Home, “to meet the needs of elderly women who had no family upon which they could rely.” (430-431)

- The Ordinance Poor Fund, which dispensed “approximately £4,000 worth of food and goods to needy people annually.” (437)

- The Ladies Benevolent Society: “a group of ladies [who had] dedicated themselves to the making and supplying of clothes for the poor.” (437)

- The Ladies Maternal Society which served “pregnant women among the London poor.” (438)

- The Flower Mission which sent flowers to hospital patients. (438)

- Hampton’s Blind Mission, including Sunday School for blind children, and a Sunday afternoon tea “for all the blind who would come.” Typically 200 (including sighted friends) did. (438)

- Thomas’ Mother’s Mission, an outreach to poor women. (438)

Drummond aptly sums up, “There seemed no end to the variety of social ministries the Metropolitan Tabernacle undertook. It was a working church.” (438)

Somehow, this dimension of C.H. Spurgeon’s legacy has been mostly lost. Maybe its recovery could close a gap in our sundered minds, lives and service in the kingdom of God.

Wouldn’t that be something!

- Gary Brumbelow

2 Comments

Jerry Miner

March 15, 2017 - 7:32 pmThanks, Darrow! Spurgeon was surrounded by friends and colleagues who thought as he did. There was no artificial divide between social and true gospel. The did not have to speak about “holism” because the gospel was comprehensive… it connected and permeated every area of life.

I think this article written by CHS shares this quite well: http://archive.spurgeon.org/s_and_t/totkc.php

Blessings!

admin

March 20, 2017 - 11:10 amJerry, Thanks for your comment and the excellent piece by Spurgeon. Indeed there was no artificial divide in him, nor was there in the men he writes about. Oh, how different our world would be if individual Christians and our churches functioned from the wholistic Biblical framework – no artificial divide!