What is the pursuit of happiness as articulated in the Declaration of Independence?

Pause for a moment and ask yourself, what does that phrase mean? And what did Thomas Jefferson, the author of the Declaration of Independence, and the others who signed it, understand it to mean?

It certainly did not have the modern hedonistic, self-serving connotation. This was not a call for individual pursuit of a narcissistic life, nor the quest of shallow, happy feelings. In fact we will see that happiness was found in what, for the modern man, was an unlikely place. It was found in the other-serving of our fellow man.

Following the Preamble, comes the Declaration of self-evident truths a government is instituted to secure.

Following the Preamble, comes the Declaration of self-evident truths a government is instituted to secure.

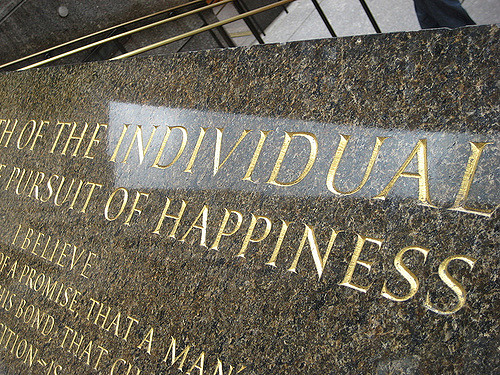

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness. — That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed ….

The United States’s founding documents, the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution, establish the high-water mark of foundational principles for civil governance.

Four observations about the pursuit of happiness

Let’s notice four things about these truths, or principles.

First, note that these truths are self-evident. Just as water is wet, the sky is blue, or the sun gives light, these truths are self-evident.

Second, while human beings are different in individual characteristics, it is self-evident that we are all of human kind as distinct from, say, reptile kind. Being equally human kind, we are created with equal value and dignity. The dignity of human life is witnessed in the account of creation in Genesis 1.

Third, humans are endowed by their Creator with unalienable rights. The rights are granted by God. They are part and parcel of what it means to be human. The rights cannot be granted or taken away by the state, by any other person or even by oneself.

These principles were acknowledged by the Founders, and their writing of these principles established the gold standard of governance. But, as is so often the case, their ideal was not their practice. A majority of the signers were slave owners. Their lives challenged the principles they espoused. The policy of “slave compromise” that allowed the Union to survive denied the principle of equal rights.

Fourth, note that these declarations develop the foundation for human rights. The document speaks of “certain unalienable Rights” including three in particular. There are others, but these are exemplars and foundational. They are the right to:

- Life – not just physical life, creature life, but the sacredness of human life. This right is denied in atheistic culture where abortion and “death with dignity” are promoted.

- Liberty – this is the freedom to be good and to do good, not the license to do evil.

- Pursuit of Happiness – The modern understanding of this phrase suffers from a certain level of murkiness.

Happiness comes from living as God directed

Two writers greatly influenced the thinking of the Founding Fathers on the concept of the pursuit of happiness. One was Sir William Blackstone (1723 – 1780), a jurist, the other, his contemporary Francis Hutcheson (1694-1746), an academic.

In his Commentaries on the Laws of England, Blackstone wrote:

In his Commentaries on the Laws of England, Blackstone wrote:

For he [the Creator] has so intimately connected, so inseparably woven the laws of eternal justice with the happiness of each individual, the latter cannot be obtained but by observing the former; and, if the former be punctually obeyed, it cannot but induce the latter.

For Blackstone, happiness is found by living within the framework of God’s eternal moral law. One finds true happiness in turning from self and self-gratification to being good and doing good. A lawless, self-absorbed life leads only to misery.

Francis Hutcheson was a theologian, philosopher, pastor and professor with a Scottish Presbyterian background. As explained in a post at Dictionary.com, Hutcheson provided

a new political interpretation of happiness to English speakers with his 1725 treatise An Inquiry into the Original of Our Ideas of Beauty and Virtue. His political philosophy: “that Action is best which accomplishes the greatest Happiness for the greatest Numbers; and that worst, which in like manner occasions Misery.” The popularity of Hutcheson’s philosophies helped tie the concepts of civic responsibility and happiness to one another in the minds of the great political thinkers of the 18th century, including the writers of the Declaration of Independence.

Hutcheson made the connection between one’s personal happiness with fulfilling one’s civic responsibilities.

Two modern authorities speak about happiness

Two recent reflections on the vision and ideals of the Founders are also helpful in our understanding of the pursuit of happiness.

Historian David McCullough, in his 2003 Jefferson Lecture “The Course of Human Events,” has written, speaking of America’s founders:

Historian David McCullough, in his 2003 Jefferson Lecture “The Course of Human Events,” has written, speaking of America’s founders:

But it is in their ideas about happiness, I believe, that we come close to the heart of their being, and to their large view of the possibilities in their Glorious Cause.

In general, happiness was understood to mean being at peace with the world in the biblical sense, under one’s own “vine and fig tree.” But what did they, the Founders, mean by the expression, “pursuit of happiness”?

It didn’t mean long vacations or material possessions or ease. As much as anything it meant the life of the mind and spirit. It meant education and the love of learning, the freedom to think for oneself.

McCullough then illustrates this with a story of George Washington.

Washington, though less inclined [than Jefferson] to speculate on such matters, considered education of surpassing value, in part because he had had so little. Once, when a friend came to say he hadn’t money enough to send his son to college, Washington agreed to help — providing a hundred pounds in all, a sizable sum then — and with the hope, as he wrote, that the boy’s education would “not only promote his own happiness, but the future welfare of others … .” For Washington, happiness derived both from learning and employing the benefits of learning to further the welfare of others.” [emphasis added]

For the founders, the pursuit of happiness had to do with free minds that pursue knowledge and virtue through the study of the arts and science, not only for one’s own edification, but ultimately for the benefit of the larger society.

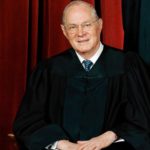

US Supreme Court Justice Anthony Kennedy made a distinction between the hedonistic concept of happiness found in modern materialistic societies and the concept of the founders. In his 2005 lecture at the National Conference on Citizenship, Kennedy noted that for the Founders, happiness meant, in contrast to its current “hedonistic component … that feeling of self-worth and dignity you acquire by contributing to your community and to its civic life.”

US Supreme Court Justice Anthony Kennedy made a distinction between the hedonistic concept of happiness found in modern materialistic societies and the concept of the founders. In his 2005 lecture at the National Conference on Citizenship, Kennedy noted that for the Founders, happiness meant, in contrast to its current “hedonistic component … that feeling of self-worth and dignity you acquire by contributing to your community and to its civic life.”

Writing under the heading “Lexical Investigations: Happiness,” an anonymous blogger has observed:

In the context of the Declaration of Independence, happiness was about an individual’s contribution to society rather than pursuits of self-gratification. While this sense has largely fallen out of use today, it’s important to keep these connotations of happiness in mind when studying political documents from the 18th century.

Most people want to be happy. But what is happiness, and how do we find it? When we pursue license and self-indulgence we find misery. Happiness is found through lives that are rich in virtue and knowledge, lives that benefit the larger community.

- Darrow Miller