Three years ago we started a series of blog posts on the subject of social justice. The term was (and still is) popular among many younger Christ followers, but not everyone has a good grasp on its biblical roots.

Three years ago we started a series of blog posts on the subject of social justice. The term was (and still is) popular among many younger Christ followers, but not everyone has a good grasp on its biblical roots.

Our posts on the subject attracted considerable attention, for which we are thankful. The upshot was the publication of Darrow’s latest book, Rethinking Social Justice: Restoring Biblical Compassion, released just last month (May 2015). It’s available from Amazon.

After reading the following post (first published in Oct 2012) you may want to order the book!

COMPASSION: The Noun That Used to Be a Verb

Compassion doesn’t mean what it used to. Not in Western cultures, at least.

One hundred fifty years ago compassion was a verb. The term meant “to compassionate, i.e., to join with in passion.”[1] Today, compassion is a noun. It has been reduced to an emotion, a synonym for pity.

As the word changed, so did the practice. At one time, people suffered together with the poor. Today, we feel guilty and write checks.

These changes are rooted in a worldview shift, from Judeo-Christian theism to secular humanism. This is the first of a short series of posts dedicated to recovering the scriptural understanding of social justice. We will study the biblical treasure trove–in both testaments–of concepts related to compassion. (You will note that we use compassion and social justice interchangeably.)

If you follow Darrow Miller and Friends, you know the importance we place on words. We in the DNA have a love for God’s word, thus we value examining the OT Hebrew and NT Greek terms behind an English word. Because the issue of social justice is so important today it is wise to understand how the word is rooted in biblical compassion.

A study of the biblical words translated “compassion” reveals three key ideas:

First, compassion springs from the heart of God. When God first describes himself to humans, he says, The LORD, the LORD, the compassionate and gracious God, slow to anger, abounding in love and faithfulness (Exodus 34:6 NIV). Without God’s intervention, the world would not know compassion, only the Darwinian animal nature of “red in tooth and claw.”

Second, compassion manifests itself in God’s steadfast love and in the incarnation of Jesus Christ. Here we see Christ suffering together with us and for our salvation.

Third, compassion is to be the hallmark of God’s people. Social justice is not an afterthought of the Christian life … it is the forethought. Christians are to be unique people, participating in Christ’s suffering, drawing alongside and suffering together with the broken and bleeding in their communities by sharing their life, time, talent, and treasure.

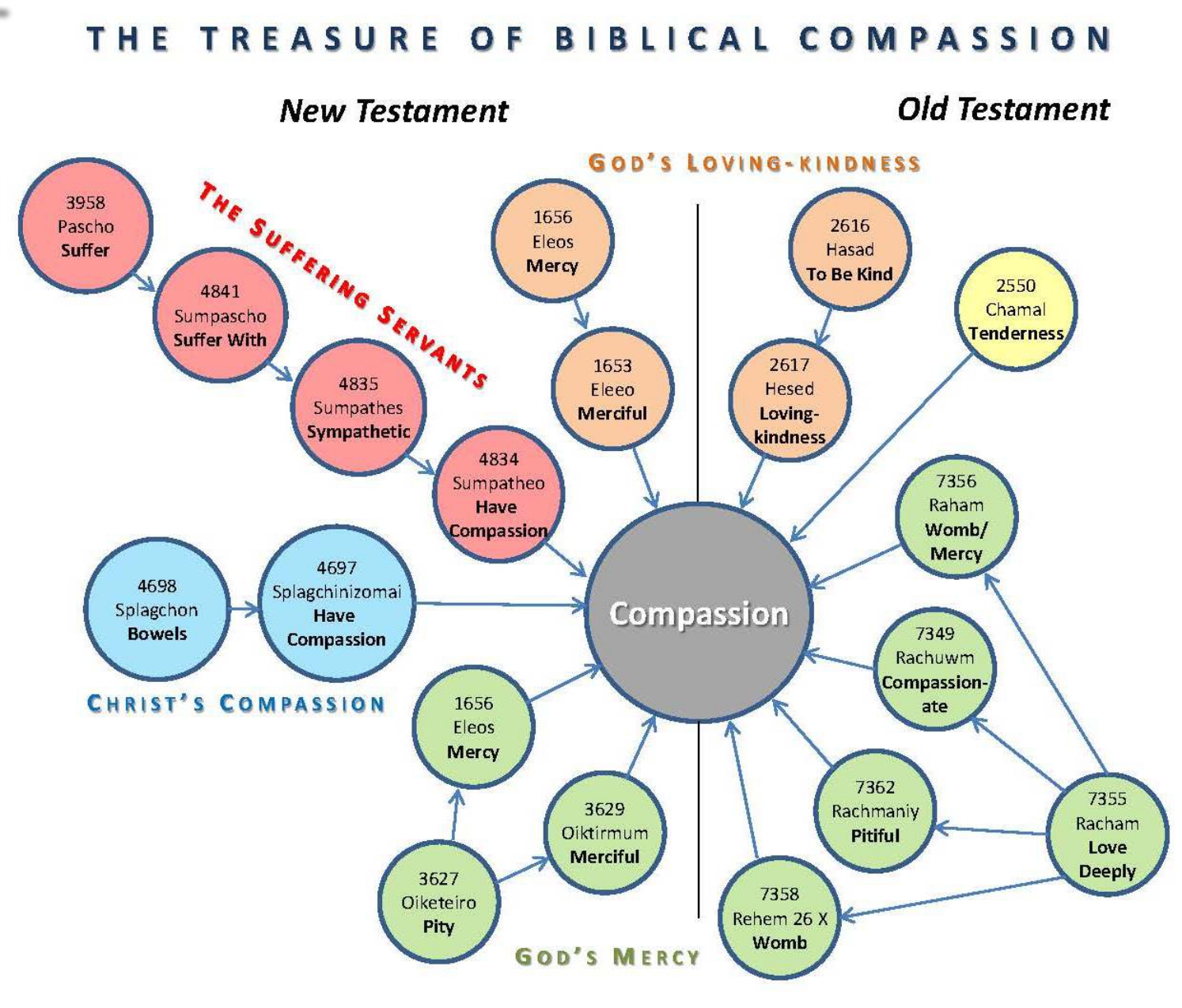

The diagram below captures the nexus (connected series) of biblical terms translated compassion.

You will note that our English word “compassion” translates three words or word families in Hebrew and two in Greek. Of these, two OT word families have their NT equivalents (see the green and tan globes that straddle the line between NT and OT). These refer to God’s lovingkindness and God’s mercy.

You will note that our English word “compassion” translates three words or word families in Hebrew and two in Greek. Of these, two OT word families have their NT equivalents (see the green and tan globes that straddle the line between NT and OT). These refer to God’s lovingkindness and God’s mercy.

These words reveal the treasure of biblical compassion. We will first consider the Old Testament concept of חָמַל (ḥā∙mǎl) – to “treat with tenderness.” Then we will study the OT-NT couplets: first the “God of mercy” – the Hebrew rahamîm and the Greek oiktirmos, and second “God’s loving kindness” the Hebrew hesed and the Greek eleos. Then we will turn to “the compassion of Christ” (the Greek family of words splanchnizomai) and “the suffering servants” (the Greek family of pascho.)

Our first example of the word compassion is the Hebrew word חָמַל (ḥā∙mǎl). The word is used 45 times in the OT. One example appears in the story of Moses’ birth. Pharaoh was fearful of the growing number of Hebrew slaves. To stem the growing tide of Hebrews he ordered their midwives to kill all newborn Hebrew boys. But the midwives feared God more than they feared Pharaoh and often hid the male infants.

When Moses was born, his mother hid him for three months. She then put him in a papyrus basket and set him in the reeds along the bank of the Nile. In God’s providence, “the daughter of Pharaoh came down to bathe at the river, while her young women walked beside the river. She saw the basket among the reeds and sent her servant woman, and she took it. When she opened it, she saw the child, and behold, the baby was crying. She took pity on him and said, “This is one of the Hebrews’ children.”

Pharaoh’s daughter demonstrated the meaning of חָמַל (ḥā∙mǎl): “show mercy on, spare, take pity on, i.e., show kindness to one in an unfavorable, difficult, or dangerous situation, and so help or deliver in some manner; to treat with tenderness; to have compassion.”

Hā∙mǎl is an emotional response that results in action. Pharaoh’s daughter did not simply feel sorry for this Hebrew baby who had been condemned to death by her father. She acted, perhaps risking her own life to have compassion on the baby Moses. She showed mercy.

As did the “righteous Gentiles” who sheltered Jews in their own homes during WWII in Germany. Sometimes their compassion cost them their lives in Hitler’s concentration camps. An example of the compassion of the righteous Gentiles is found in the story of Corrie ten Boom in the book and movie The Hiding Place.

As did the “righteous Gentiles” who sheltered Jews in their own homes during WWII in Germany. Sometimes their compassion cost them their lives in Hitler’s concentration camps. An example of the compassion of the righteous Gentiles is found in the story of Corrie ten Boom in the book and movie The Hiding Place.

Another, less-known example of biblical compassion is that of Paul Rusesabagina, manager of the Hôtel des Mille Collines in Kigali, Rwanda. Rusesanagina provided shelter and protection for 1,268 Hutu and Tutsi refugees to keep them from being killed by the Interahamwe Militia ravaging Rwanda. His story is told in the movie Hotel Rwanda.

Another, less-known example of biblical compassion is that of Paul Rusesabagina, manager of the Hôtel des Mille Collines in Kigali, Rwanda. Rusesanagina provided shelter and protection for 1,268 Hutu and Tutsi refugees to keep them from being killed by the Interahamwe Militia ravaging Rwanda. His story is told in the movie Hotel Rwanda.

These are examples of ḥā∙mǎl writ large. There are millions of smaller acts of showing mercy around the world every day.

– Darrow Miller with Gary Brumbelow

7 Comments

Gayle Frazer

February 25, 2015 - 5:51 pmI have been studying the word Compassion and agree its a verb!!!

admin

February 26, 2015 - 12:40 pmGood for you, Gayle. And the distinction is important, eh? It’s a reminder that true compassion takes action.

Darrow’s latest book, Rethinking Social Justice: Restoring Biblical Compassion” explores this theme and its implications. Stand by for publication later this spring.

Gary Brumbelow