The grainy screen grab captures a heroic moment in Dallas, Texas, last month. A woman on a motorcycle was hit by a vehicle and dragged underneath. She was saved when police officers, firefighters and witnesses lifted the car and pulled her to safety.

The grainy screen grab captures a heroic moment in Dallas, Texas, last month. A woman on a motorcycle was hit by a vehicle and dragged underneath. She was saved when police officers, firefighters and witnesses lifted the car and pulled her to safety.

Police officers and firefighters are supposed to do things like that. But why did the “witnesses” help? Why risk injury to save a stranger?

Recently a Facebook video showed a man standing on a bridge, poised to leap to his death. Firefighters were able to snatch him away and save his life. That’s what they do; they’re professional lifesavers, and thank God for them. But at least two civilians were also involved. One was with the despondent man, filming and talking to him. Another alerted the firefighters to the situation. Nobody paid them to do this. Why would strangers intervene for a bridge jumper?

This is especially noteworthy in view of the doctrine of the fall. Our imago Dei ancestors rebelled, and that image of God was marred. In some theological frameworks, the fall renders humans selfish and unconcerned about others. This view has a hard time accounting for anyone doing good deeds for strangers.

But the fall did not demolish God’s image in the human. The image was marred. Badly distorted, but not eradicated. Thus every good deed springs from God’s image in the human. As God-image bearers, humans have the ability and responsibility to make visible God’s invisible attributes. God created us (male and female) as his representatives, stewards of his creation and agents of His reputation and mission in the world (see Gen 1:26-28; 2:15-17; 9:6; Psa. 8:5).

That’s why bystanders jump in to help someone they don’t know. People are hard-wired to do good. Notwithstanding the fact that doing good cannot redeem us to God (Isaiah 64:6; Romans 7:18), without question, the world is a better place when humans act on these God-implanted instincts.

Lydia Sigourney, a maternal feminist of another day, called doing good a “science.” She wrote as a Christian who understood and acknowledged the effects of the fall, but also the doctrine of common grace.

It is doubtless evident to you, that I speak of the science of doing good. Yet I would not confine the term to its common acceptation of alms-giving. This is but a single branch of the science, though an important one. A more extensive and correct explanation is, to strive to increase the happiness, and diminish the amount of misery among our fellow creatures, by every means in our power. This is a powerful antidote to selfishness, that baneful and adhesive disease of our corrupt nature, or to borrow the forcible words of Pascal, that ‘bias towards ourselves, which is the spring of all disorder.’” Letters to Young Ladies, p. 189

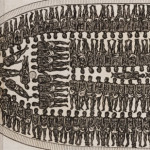

Another example, largely unknown today, is Hannah More, the female counterpart to William Wilberforce, noted by historians as “the single most influential woman in the British abolistionist movement.” Like Wilberforce, she made a nuisance of herself the evils of the slave trade, ambushing unsuspecting dinner guests with a (now-famous) print depicting the unspeakable fashion by which the maximum number of Africans were crammed in the hold of a slave ship.

Another example, largely unknown today, is Hannah More, the female counterpart to William Wilberforce, noted by historians as “the single most influential woman in the British abolistionist movement.” Like Wilberforce, she made a nuisance of herself the evils of the slave trade, ambushing unsuspecting dinner guests with a (now-famous) print depicting the unspeakable fashion by which the maximum number of Africans were crammed in the hold of a slave ship.

Karen Swallow Prior, writing in the March 4, 2015 issue of Christianity Today, notes that,

“What William Wilberforce was among men, Hannah More was among women.” So the Christian Observer proclaimed upon More’s death in 1833. Wilberforce, the parliamentarian and politician, was the most public face of the campaign, and today is nearly synonymous with the British abolitionist movement. By contrast, as a woman who could not even vote or join abolitionist societies of the day, More was destined for obscurity. Yet historians agree she was the single most influential woman in the British abolitionist movement. One biographer said her efforts formed “one of the earliest propaganda campaigns for social reform in English history.”

Once a celebrated literary figure, More (1745–1833) was a close friend of Wilberforce. And like him, she was a tireless force for abolition and reform of British society from high to low. But unlike Wilberforce—who is still celebrated in best-selling biographies and movies—More is largely unknown outside her home region near Bristol.

Every time a human does good for a stranger, a little picture of the kingdom of God is emerging. Every instance of truth, or beauty, or goodness reminds us that One has come who turned our upside down world rightside up again, who is even now drawing history toward that final day of light and life and joy when the fall and all its ugly effects will be rolled back on itself and all will be glorious and new.

- Gary Brumbelow