In the previous post I introduced a recent talk by Charles Chaput, the Archbishop of Philadelphia, on the church’s response to secularized culture. At the end of that post, I quoted Chaput as follows:

Apostasy is an interesting word. It comes from the Greek verb apostanai – which means to revolt or desert; literally ‘to stand away from.’ [Christians] … don’t need to publicly renounce their baptism to be apostates. They simply need to be silent when their … faith demands that they speak out; to be cowards when Jesus asks them to have courage; to ‘stand away’ from the truth when they need to work for it and fight for it” (emphasis added).

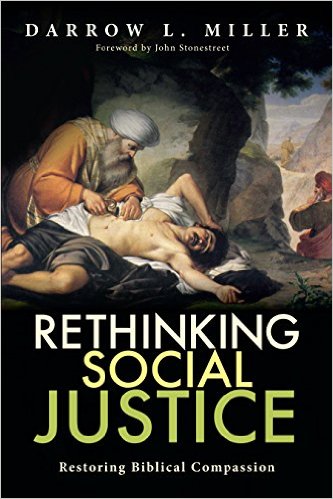

From there, he went on to describe the values our increasingly secularized culture upholds—values rooted in atheistic postmodernism infused with a strain of neo-Marxism. The highest value—the greatest good—is a radical form of individual sovereignty and autonomy, combined with radical egalitarianism. We’ve addressed this  topic before in this blog post, as well as in our book, Reclaiming Social Justice: Restoring Biblical Compassion. Here’s what Archbishop Chaput said about it:

topic before in this blog post, as well as in our book, Reclaiming Social Justice: Restoring Biblical Compassion. Here’s what Archbishop Chaput said about it:

I’m committing a primal American heresy — we’re not created ‘equal’ in the secular meaning of that word. We’re obviously not equal in dozens of ways: health, intellect, athletic ability, opportunity, education, income, social status, economic resources, wisdom, social skills, character, holiness, beauty or anything else. And we never will be. Wise social policy can ease our material inequalities and improve the lives of the poor. But as Tocqueville warned, the more we try to enforce a radical, unnatural, egalitarian equality, the more ‘totalitarian’ democracy becomes.

[Liberal progressivism] proceeds from the idea that we’re born as autonomous, self-creating individuals who need to be protected from, and made equal with, each other. It’s simply not true. And it leads to the peculiar progressive impulse to master and realign reality to conform to human desire, whereas the Christian masters and realigns his desires to conform to and improve reality.

That last sentence is a very powerful summary of the two utterly incompatible worldviews that are contesting for the hearts, souls and minds of our culture today. One seeks to “master and realign reality to conform to human desire,” whereas the other “realigns [human] desires to conform to and improve reality.”

Those who hold the latter view are heading into some very trying times. Those of us who bow only to the true King of kings will increasingly be slandered as bigots and haters. We will be banned, fined, fired, silenced, and otherwise pushed to the margins of the society.

So how do we respond? Here, Archbishop Chaput offers helpful pastoral advice. We must not lose heart or succumb to fear. Rather, we must cling ever more tightly to God, and to the truth. The oft-repeated refrain of Scripture is this: “Trust God, and fear not.” Archbishop Chaput reminds us that:

Serenity of heart comes from consciously trying to live on a daily basis the things we claim to believe. Acting on our faith increases our faith. And it serves as a magnet for other people. To reclaim the Church … we should start by renewing in our people a sense that eternity is real, that together we have a mission the world depends on, and that our lives have consequences that transcend time.

The hijab in America indicates resistance to secularized culture

He continues:

In Philadelphia I’m struck by how many women I now see on the street wearing the hijab or even the burqa. Some of my friends are annoyed by that kind of “in your face” Islam. But I understand it. The hijab and the burqa say two important things in a morally confused culture: ‘I’m not sexually available;’ and ‘I belong to a community different and separate from you and your obsessions.’

In Philadelphia I’m struck by how many women I now see on the street wearing the hijab or even the burqa. Some of my friends are annoyed by that kind of “in your face” Islam. But I understand it. The hijab and the burqa say two important things in a morally confused culture: ‘I’m not sexually available;’ and ‘I belong to a community different and separate from you and your obsessions.’

I have a long list of concerns with the content of Islam. But I admire the integrity of those Muslim women. And we need to help [Christians] recover their own sense of distinction from the surrounding secular meltdown. The Church … can never be fully integrated [into our contemporary culture] without eviscerating the Christian faith. An appropriate ‘separateness’ for [the Church] is already there in the New Testament. We’ve too often ignored it because Western civilization has such deep Christian roots. But we need to reclaim it, starting now.

I can’t emphasize that enough. If we think we can continue with one foot in a highly secularized culture that has abandoned God and values human autonomy above all else, while we keep the other foot in the church that proclaims the Lordship of Jesus Christ and Him alone, we are fooling ourselves. Choices will have to be made, and sadly, many are opting to leave the church in favor of the culture. But as Archbishop Chaput rightly said, “We should never be afraid of a smaller, lighter Church if her members are also more faithful, more zealous, more missionary and more committed to holiness. Making sure that happens is the job of those of us who are [leaders of the church].”

He continues:

Losing people who are members of the Church in name only is an imaginary loss. It may in fact be more honest for those who leave and healthier for those who stay. We should be focused on commitment, not numbers or institutional throw-weight. We have nothing to be afraid of as long as we act with faith and courage.

Here’s his powerful conclusion:

When I was ordained a bishop, a wise old friend told me that every bishop must be part radical and part museum curator – a radical in preaching and living the Gospel, but a protector of the Christian memory, faith, heritage and story that weave us into one believing people over the centuries.

I try to remember that every day. Americans have never liked history. The reason is simple. The past comes with obligations on the present, and the most cherished illusion of American life is that we can remake ourselves at will. But we Christians are different. We’re first and foremost a communion of persons on mission through time – and our meaning as individuals comes from the part we play in that larger communion and story.

If we want to reclaim who we are as a Church … we need to begin, in ourselves and in our local [churches], by unplugging our hearts from the assumptions of a culture that still seems familiar but is no longer really ‘ours.’ It’s a moment for courage and candor, but it’s hardly the first moment of its kind.

Amen, and amen.

- Scott Allen