For centuries, the history of technological development was largely driven by Christ followers motivated by their belief-system to ease human labor, reduce human suffering, and generally improve the lives of imago Dei humans. Technological development has often been inspired by the biblical concept of shalom.

More recently, after several generations of materialist indoctrination in the West, we have seen the divorcing of the Judeo-Christian worldview from technology’s advancement. That divorce has included abandoning moral considerations (“ought we”) in favor of merely pragmatic concerns (“can we”).

Ought we to do it because we can do it?

“Ought we to do it?” is a moral question. “Can we do it?” is a pragmatic question.

Today we live in a “brave new world” where we answer the second question without considering the first.

In other words, today, moral considerations have been abandoned; we live in a world of pragmatism. If something is useful, it must be the right thing to do, it must be “good.” If something is not useful, it is by definition, “bad.”

The men and women who led the founding of modern science and her daughter technology lived in a moral universe and functioned from a wholistic paradigm. The morality question preceded the practicality question.

Jacques Ellul (1912-1994) was a French historian, sociologist, and lay theologian. With his characteristic prescience, Ellul wrote in 1954, “No social, human, or spiritual fact is so important as the fact of technique in the modern world. And yet no subject is so little understood.” Today we live in a godless universe with no moral framework. The only relevant question is “Can we do it?” As a result, we are moving with breakneck speed into the unknown of human cloning.

With the rise of industrialization, we put our minds to work to make things out of inanimate materials that would be useful to mankind. We created the steam engine, then the gas engine. We attached the engines to bicycles and made motorcycles. We strapped them to wings and made airplanes. We created the assembly line to mass produce. We made things better and better and faster and faster.

Then we turned our attention to mass producing food to feed more and more people and feed them more efficiently.

Two hundred years ago, the majority of people in the USA lived on farms or had gardens and grew enough food to feed their families. (There are still places in the world today where the average farmer dies not produce enough food to feed his own family.) In 1940, the average American farmer produced enough food to feed 19 people. Today, through the development of industrial farming, the average farmer can feed 155 people. Less than two percent of Americans live on farms today and they produce enough food to feed the USA and much of the world.

In other words, industrial, mass production methods were applied to living things, to plants.

Then the industrial mentality turned to farm animals. The idea was to treat cows as milk producers, steers as meat producers, and chickens as egg producers. Now animals with breath in their bodies were no longer treated as creatures, but as machines.

Today, early in the 21st century, we are beginning to treat human beings as machines. And why not? If a human is not made in God’s image (because there is no God) but is merely a very complex machine, there is no reason not to treat humans as machines.

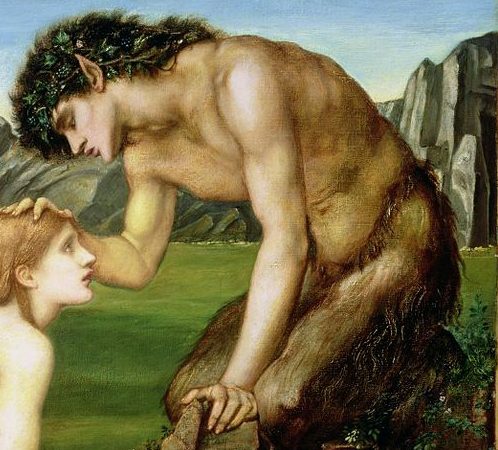

We are currently creating human-animal hybrid embryos, which are “allowed” to live for up to 14 days, before they are “harvested” for research purposes. These hybrid creatures are called chimeras, after the Greek mythological creature with a goat’s body, a lion’s head and a serpent’s tail.

Around the world scientists are creating human-animal embryos. One of the near term goals is to use human-pig embryos to be incubators for growing human organs including livers, kidneys, lungs, hearts, pancreases and corneas.

We can create human-animal embryos. No doubt it will soon be possible to develop these embryos further and actually bring them to “birth.” Perhaps such a creature exists in a lab somewhere even now. We can (tomorrow if not today), but should we? Ought we to do this? Who is asking the moral question? Does today’s science even have a framework for a moral discussion?

Wesley J. Smith is a senior fellow at the Discovery Institute’s Center on Human Exceptionalism. Smith writes:

Wesley J. Smith is a senior fellow at the Discovery Institute’s Center on Human Exceptionalism. Smith writes:

With so much humanity-altering power being developed, where are the democratic debates about whether we should permit human beings to be designed, manufactured, and subjected to methods of quality control?

Are we actually moving into the industrialization of human beings? In the internal framework of our minds and hearts we have already erased the concept of humanity by denying the One who made us human in the first place. Will we soon cross the same line in the external world? Will we literally reduce human beings to the level of our vain imagination, the level of mere machinery? Who will raise these questions? Where is the public arena where these questions will be discussed?

Writing in First Things, Smith says this slide into oblivion can be stopped.

It doesn’t have to be that way. We need not helplessly, passively, watch biotechnology’s power and influence surge. We can shape biotechnological advances to achieve moral ends. But that will require far more consideration of these issues than we have yet given them.

What will you do? Will you raise this question in your circle of friends, in school, at work and at church? Will you begin to ask the moral question in public, “Ought we to do this?”

For more on this subject read: BRAVE NEW WORLD SHOULD BE AN ELECTION ISSUE

- Darrow Miller