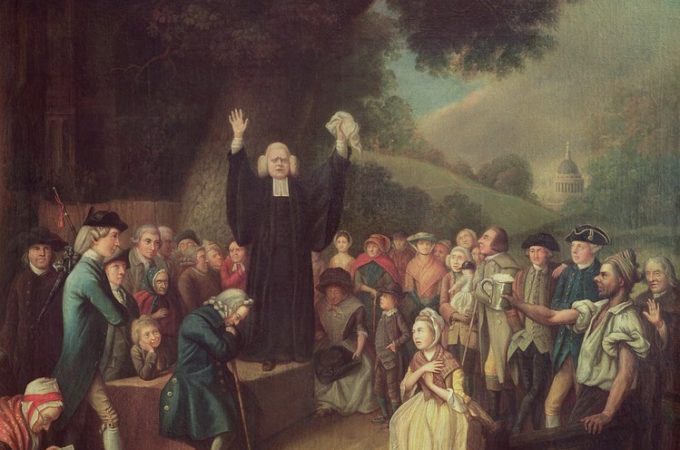

Colonial preachers such as George Whitefield energized the American Revolution

From the mid-1600s to the mid-1800s, public schools as we know them today were virtually nonexistent. Parents, pastors, and tutors taught the rising generation how to read, write, and cipher and how to think and reason using the Bible as their primer or first book of instruction. In these 200 years, America produced five generations of extraordinary men and women who laid the foundation for a nation dedicated to the Christian principle of liberty and the art of self-government.

The private system of education in which our forefathers were educated included home, school, church, voluntary associations such as library companies and philosophical societies, circulating libraries, apprenticeships, and private study. It was a system supported primarily by private benefactors, although there was a veneer of government involvement in some colonies, such as in Puritan Massachusetts. All was done without compulsion.[1]

The Old Deluder’s Law of 1642 was passed in the Massachusetts colony. It stated: “All youth are be taught to read perfectly the English tongue, have knowledge in the laws and be taught some orthodox catechism.” Colonial America also had dame schools, in which neighborhood children were taught to read and write by women in their own kitchens.

Unlike modern America, in which the most influential voice in the culture is the media, in colonial America the pulpit served as the single most powerful voice to inspire the thinking and reasoning of the colonists. What fired the colonial pulpit was the influence of Reformers John Knox and John Calvin. Their teachings on the Kingdom of Christ and the authority of the Scripture gave rise to the colonial form of self- and civil government.

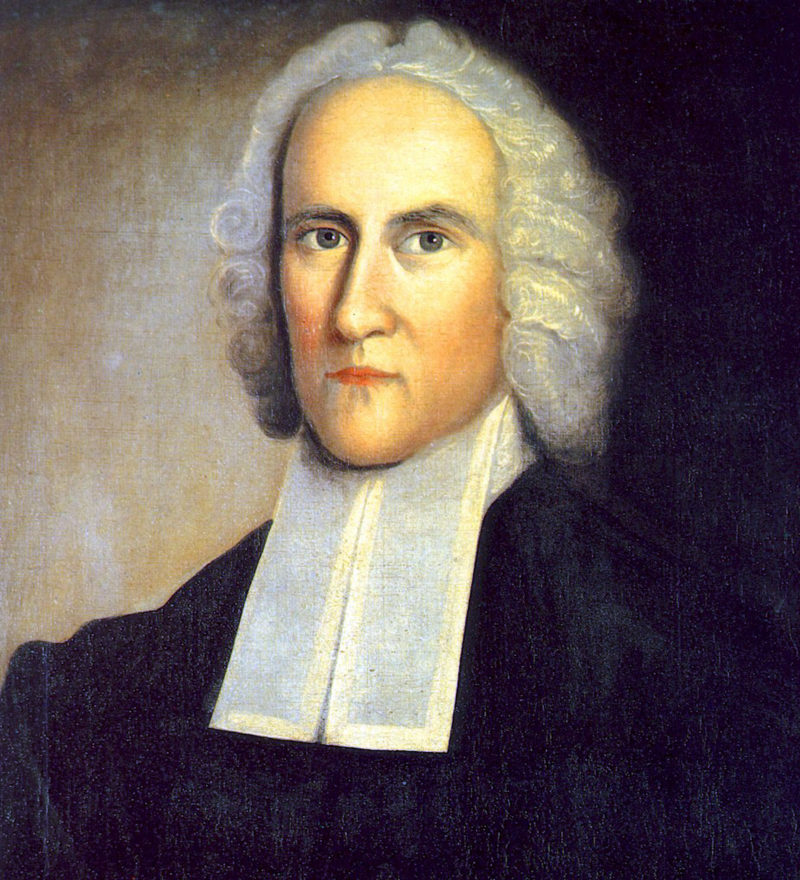

The colonial pulpit, which began with men like Joseph Cotton, 1630 Puritan pastor of Boston, remained for 150 years the primary educational influence for the colonials through the preaching of such clergymen as Cotton Mather, Jonathan Edwards (evangelical patriarch), George Whitefield (First Great Awakening), Dr. John Witherspoon (signer of the Declaration of Independence), Samuel Davies (pastor of Patrick Henry), Jonas Clark (Lexington, 1775), and Peter Muhlenburg (“Give ‘em Watts, boys!”), to name just a few. These were giants indeed, men who faithfully led their congregations to think biblically. Some clergy even donned the garb of soldier during the American Revolution to fight tirelessly with pen and sword for the cause of Christian civilization on the North American continent. According to Yale historian, Harry S. Stout,

The colonial pulpit, which began with men like Joseph Cotton, 1630 Puritan pastor of Boston, remained for 150 years the primary educational influence for the colonials through the preaching of such clergymen as Cotton Mather, Jonathan Edwards (evangelical patriarch), George Whitefield (First Great Awakening), Dr. John Witherspoon (signer of the Declaration of Independence), Samuel Davies (pastor of Patrick Henry), Jonas Clark (Lexington, 1775), and Peter Muhlenburg (“Give ‘em Watts, boys!”), to name just a few. These were giants indeed, men who faithfully led their congregations to think biblically. Some clergy even donned the garb of soldier during the American Revolution to fight tirelessly with pen and sword for the cause of Christian civilization on the North American continent. According to Yale historian, Harry S. Stout,

Over the span of the colonial era, American ministers delivered approximately eight million sermons, each lasting one to one-and-a-half hours. The average 70-year-old colonial churchgoer would have listened to some 7,000 sermons in his or her lifetime, totaling nearly 10,000 hours of concentrated listening. This is the number of classroom hours it would take to receive ten separate undergraduate degrees in a modern university, without ever repeating the same course![2]

The sermon provided colonial families an excellent educational experience. Sunday morning was not only a time to hear the latest news and see old friends, but it was also an opportunity to sit under a man of God who had spent many hours preparing for a two, three, or even four-hour sermon. Many a colonial pastor spent eight to twelve hours daily studying, praying over, and writing his sermon. Unlike sermons on the frontier in the mid-19th century, colonial sermons were filled with the fruits of years of study. They were geared not only to the emotions and will, but also to the intellect.

The sermon was one of the chief literary genres in colonial America. Listeners followed sermons closely, took mental notes, and discussed the message with their family on Sunday afternoon. Thus, without ever attending a college or seminary, a churchgoer in colonial America could gain an intimate knowledge of Bible doctrine, church history, and classical literature. Questions raised by the sermon could be answered by the pastor or by books in church libraries that sprang up all over the colonies. Often sermons were published, and listeners could review what they had heard on Sunday morning. They were often passed from family to family in a community, as fathers sat nightly with their families around the fireplace rereading the Scriptural references aloud and reviewing each principle with their children. Parents and pastors took seriously their role to educate both the head and the heart.

Sermons were also delivered on various public occasions, such as Days of Thanksgiving or Fasting and the election of officers of the local militia. They were often printed as political pamphlets, as pastors in the 17th and 18th centuries delivered dissertations on civil government. “The annual ‘Election Sermon’—a perpetual memorial that continued down through the generations from century to century—still bears witness [1860] that our forefathers ever began their civil year and its responsibilities with an appeal to Heaven, and recognized Christian morality as the only basis of good laws.”[3]

The years 1740 to 1790 marked an age of “mighty men of God!”—an era of remarkable patriot-preachers who, by their faithful preaching and their righteous lifestyle, laid the foundation for the American Revolution and the founding of the new Republic. “To the Puritan pulpit we owe the force that won our independence.”[4] England’s King George III referred to the Revolution as the “Parson’s Rebellion.”

George Bancroft, 19th century statesman and historian wrote, “the Revolution of 1776, so far as it was affected by religion, was a Presbyterian measure. It was the natural  outgrowth of the principles which the Presbyterianism of the Old World planted in her sons in the New World—the English Puritans, the Scottish Covenanters, the French Huguenots, the Dutch Calvinists, and the Presbyterians of Ulster [Ireland]. … The American Revolution was but the application of the principles of the Reformation to civil government.”[5]

outgrowth of the principles which the Presbyterianism of the Old World planted in her sons in the New World—the English Puritans, the Scottish Covenanters, the French Huguenots, the Dutch Calvinists, and the Presbyterians of Ulster [Ireland]. … The American Revolution was but the application of the principles of the Reformation to civil government.”[5]

Presbyterian Scotsman, Dr. John Witherspoon, was president of the College of New Jersey (now Princeton University) and was especially prominent in the independence movement. His influence as a pastor/educator was enormous. One crown official in the colonies wrote back to England that the labors of such clergymen as John Witherspoon so influenced the shape of the conflict that it had very much become a religious war. Witherspoon tutored James Madison, architect of the Constitution and U.S. President, Vice-President Aaron Burr, nine cabinet officers, 21 U.S. Senators, 39 Congressmen, three Supreme Court justices, 12 state governors, and numerous ministers, lawyers, judges, and other public officials. Five of the 55 members of the Constitutional Convention were his students. He nurtured a whole generation of statesmen with the Scriptures and the Covenanter’s view of civil government. He was elected as a delegate from New Jersey to the Continental Congress and served for five years. He was the only clergyman to sign the Declaration of Independence, and during his period in Congress he served on over 120 committees. “One realizes after seeing the character of these men why it is said that the colonists treated them with the kind of reverential regard that they refused to give kings and Anglican bishops.”[6]

The true alliance between politics and religion is the lesson that was inculcated by the colonial clergy. “The pulpit of the Revolution is the voice of the Founding Fathers of the Republic, enforced by their example. They invoked God in their civil assemblies, called upon their chosen teachers of religion for counsel from the Bible, and recognized its precepts as the law of public conduct.”[7] They prepared the new nation for the struggle for liberty with the Word of God and a deep trust in Him in their hearts. This was the colonials’ source of moral energy.

The results of colonial education are most impressive. America’s educational institutions—family, church, and school—produced generations of articulate, Christian men and women who could discourse on complex issues of self- and civil government. Samuel Adams, colonial patriot and father of the American Revolution, summarized the ideal of American colonial education: “To develop a wise and virtuous man, fit to be trusted with the liberty of his country.”[8]

– Elizabeth Youmans

[1] Carson, C. (1960). The American Tradition. The Foundation for Economic Education, Inc.

[2] Christian History Magazine, Issue 50: Christianity and the American Revolution

[3] Hall, V. (1976). Christian History of the American Revolution. Foundation for American Christian Education.

[4] Thornton, J. W. (1860). The Pulpit of the American Revolution. Reprinted by Bibliobazaar (2008). Preface.

[5] Bancroft, G. (1875). History of the United States of America from the Discovery of the Continent, Vol. X. Little, Brown and Co., p. 310.

[6] Adams, J. L. (1989) Yankee Doodle Went to Church: The Righteous Revolution. F.H. Revell.

[7] Thornton, J. W. (1860). The Pulpit of the American Revolution. Reprinted by Bibliobazaar (2008), Preface.

[8] Speech delivered in Boston, October 4, 1790.