Fifty years ago, watching Francis Schaeffer write on a napkin, I learned something important about the nature of truth. And I’m still reflecting on that evening with Dr. Schaeffer at his mountain home, Chalet Les Melezes, in Huemoz, Switzerland.

What he said that night and the diagrams he drew on a napkin answered so many questions, profoundly shaping my thinking and what I would write later in life. What he shared was very insightful, but, to my knowledge, it was never put in print.

The year before my wife and I were at L’Abri, I was a student at an evangelical seminary in Denver, Colorado. I was working as a Young Life club leader at the inner city Manual High School. As a young “social activist,” desiring to work in communities of poverty, my interest lay in finding ways to help improve the lives of young, disadvantaged, and inner city high school students.

But in seminary, between hearing lectures and reading, our free time was devoted to “solving” some of the Christian world’s intractable theological problems. We had endless discussions, with very little progress, on such subjects as Calvinism vs. Arminianism, grace vs. law, free will vs. predestination, faith vs. works, and human responsibility vs. God’s sovereignty. While these questions are significant, the frustration of endless arguments wore on me, especially when compared to the pressing needs in downtown Denver where I ministered. For this reason, I took the next year off to “get my head screwed on straight.” After studying for five months in Israel, Marilyn and I thumbed our way through Turkey, Greece, Yugoslavia, Italy and made our way up to L’Abri – The Shelter, in the Swiss Alps.

Two concepts of truth

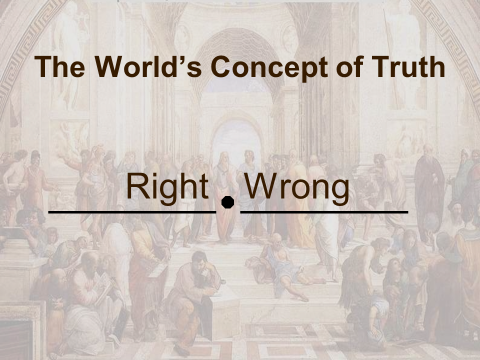

One night, it must have been over dinner at Schaeffer’s home, he drew a picture on a napkin of a dot on a line and said, “This is the world’s concept of truth: the point on the line marks the demarcation between truth and falsehood. Those on one side are right, those on the other side are wrong.”

I realized that this was exactly what we were doing in our endless seminary discussions. I also recognized that, inherently, if the point on the line is a demarcation between right and wrong, one will want to stay as far away as possible. This necessarily feeds the tendency to move to extremes.

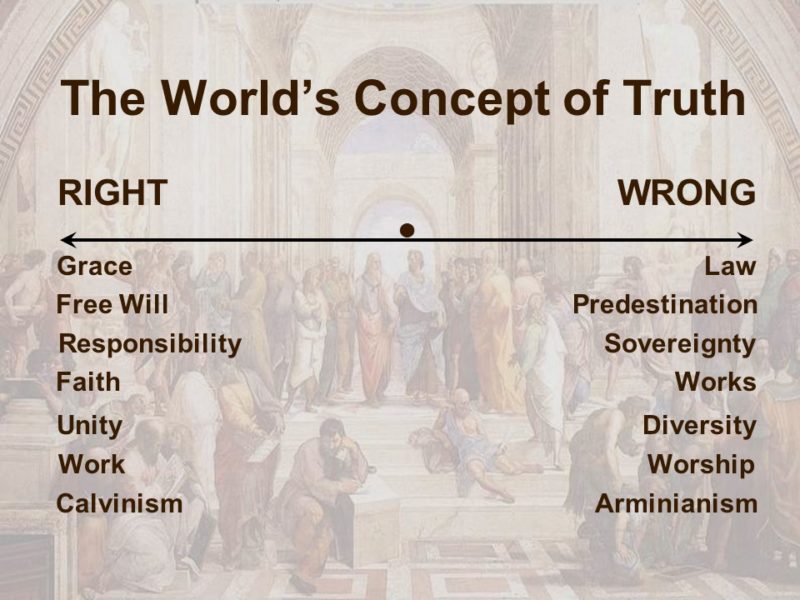

Schaeffer’s point applied to those seminary discussions can be visualized like this.

This approach to truth creates conflict and even unnecessary division. One is forced to choose one side or the other. This results in a hierarchy of, say, law over grace. One could be set aside for the other; that is, grace affirmed and law swept under the rug, or vice versa.

We see this division in the New Testament between the Judaizers who promoted the law at the expense of grace, and the libertines who promoted grace at the expense of law. Neither sought nor achieved a biblical harmony between two principles, both clearly taught in the scripture.

Here’s how the Apostle Paul addressed the relationship between law and grace.

So since God’s grace has set us free from the law, does this mean we can go on sinning? Of course not! (Ro. 6:15 NLT)

Well then, if we emphasize faith, does this mean that we can forget about the law? Of course not! In fact, only when we have faith do we truly fulfill the law. (Ro. 3:31 NLT)

Schaeffer said, “In this fallen world, things constantly swing like a pendulum, from being wrong in one extreme way to being wrong in another extreme. The devil never gives us the luxury of fighting on only one front, and this will always be the case.”

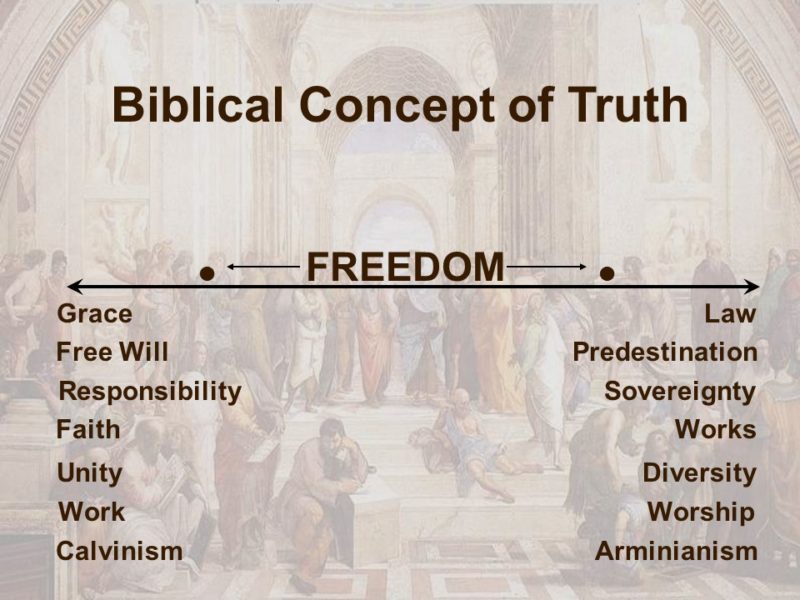

Then Dr. Schaeffer drew another picture and said that biblical truth is marked by two points on a line, and that there is freedom to live within these points.

Truth is found between the two points. Error is found outside the points on either side. He illustrated the concept as an elevated road where one could fall off into the ditch on either side, or a pinnacle where there is a cliff on both sides. If you saw only the cliff on one side and backed up from the danger in front of you, you could easily fall off the cliff on the other side.

Monument Valley, in northern Arizona, pictures the danger perfectly. To survive on top of the pinnacle one needed to keep both precipices in view.

Schaeffer’s comments and napkin diagrams created a paradigm shift for me that has been helpful ever since. Coming to an apparent contradiction, in my own reflections or in conversation, I have remembered the napkin talk and sought ways to find harmony and avoid either precipice.

Christ speaks of “the straight and narrow way” in relationship to our salvation.

Enter through the narrow gate. For wide is the gate and broad is the road that leads to destruction, and many enter through it. But small is the gate and narrow the road that leads to life, and only a few find it. Matthew 7:13-14

This straight and narrow way also describes the process of seeking the divine harmony of what seemingly had been irreconcilable differences found in biblical teaching.

Some beliefs are actually irreconcilable

Of course some positions are indeed irreconcilable because they are built on principles derived from radically different paradigms. We see this in the paradigm differences between, for example, atheism and biblical theism, or postmodernism and biblical theism. As Francis Schaeffer said in The Christian Manifesto,

These two worldviews [Judeo-Christian theism and Secular Humanism] stand as totals in complete antithesis to each other in content and also in their natural results —including sociological and governmental results, and specifically including law. …. It is not that these two worldviews are different only in how they understand the nature of reality and existence. They also inevitably produce totally different results. The operative word here is inevitably. It is not just that they happen to bring forth different results, but it is absolutely inevitable that they will bring forth different results.

The atheistic worldview of secularism and the theistic worldview of the Bible articulate very different concepts of human life. One posits that we are simply animals or complex machines, the product of a cosmic accident. The other affirms that we are the very image of God, that human life is sacred and was created for a divine purpose.

These two radically different paradigms produce different principles, the “right to choose” and the “right to life.” On the level of principle these two positions are irreconcilable. One might find some common ground on the level of policy, such as promoting adoption to save the life of the baby. But, generally, different paradigms lead to different principles, policies and programs.

Suggested solutions for seemingly irreconcilable differences

As for the seemingly irreconcilable differences, we can extend Schaeffer’s napkin drawing to illustrate the solution to some of these. Christians have opportunity to seek “middle ground” between the pendulum extremes. On that middle ground we can stand together to wage battle against the true enemies of the cross. After all, the cross of Christ is the place where the radical integration of love and justice is manifest.

To say it differently, Christians are to be counter cultural, avoiding conformity in either extreme. If we are comfortable with the status quo of the right or the left, we have succumbed to the culture.

Instead of fixating on our differences with other Christ followers, we can find common ground within the divine framework. We need not be paralyzed by arguments in any of these scales: law vs. grace, free will vs. predestination, faith vs. works, unity vs. diversity, sovereignty vs. human responsibility, work vs. worship, et al. Here is a realm of new thinking and high adventure, not the easy way that takes little effort, that leads to unnecessary conflict and curtails fruitfulness.

The place we find ourselves within the framework at any one time will be determined by two things: our personalities and our circumstances.

Some people are more grace oriented by nature and some more law oriented. The former need to consciously keep the law of God in view to avoid libertinism. The latter need to keep their eyes on grace to avoid antinomianism.

Our circumstances also influence where we will fall on the scale. If one is confronting a drug dealer, a greater focus on law may be appropriate. On the other hand, ministering to the victim of a drug dealer will call for more grace.

Keeping both boundaries in mind will help one navigate the narrow path on top of the pinnacle. My hope is that the story of the napkin conversation will have a similar impact on your life and thinking.

Thank you, Dr. Schaeffer, for drawing that revolutionary diagram on your napkin almost 50 years ago. That napkin conversation changed the tenor and direction of my life.

- Darrow Miller

2 Comments

Peter Millward

July 12, 2018 - 11:30 amDarrow – This is so good to read! This year I returned to the scripture I have often visited over the years with my pictures – The Broad and the Narrow Way. I am studying and preparing a book about the picture by Mrs Charlotte Reihlen…..there is a lot of study involved….But what Dr Schaeffer is saying is so true….thank you for sharing….I am absorbing this picture of two points by Dr Schaeffer. Interestingly I had a question in my mind as I looked at different versions for the Broad and Narrow Way…..some which proceeded the well know version by Charlotte Reihlen. They usually have just two ways either left or right in a picture….but I saw one picture….which seems to place the narrow way weaving its way upwards…on one side showing the broad road – but also on the right hand side it seemed to be showing the challenges and dangers Christians will face – attacks from satan, and various temptations as they travel the narrow Way. So the picture of the truth by Schaeffer being actually between two points I think is a good one…..we can fall off the edge in various ways on the narrow path of life. On either side of two points can be just as equally dangerous and to be avoided….I think of the scripture, “Watch your life and doctrine closely. Persevere in them, because if you do, you will save both yourself and your hearers.”. 1 Timothy 4:16 The words of Jesus should always be the centre to anchor our lives in the centre line of two points to walk in.

admin

July 17, 2018 - 4:57 amPeter

Thank you for your thoughtful response to this posting. In thinking about what you have written and the images you have conveyed, it made me think of both Bunyan’s Pilgrims Progress and Lewis’ The Horse and His Boy.

Blessings on you, my brother.