“Compassion” has become one of a growing number of politicized words (like ‘access’ or ‘diversity’) whose meaning has been corrupted beyond redemption.

So writes Thomas Sowell the Rose and Milton Friedman Senior Fellow at The Hoover Institution of Stanford University. While I would agree with Sowell that the word has been corrupted–it is in fact merely a shadow of its past glory–I don’t agree that it is beyond redemption. Compassion is the very nature of God. Although the glory of the word’s meaning has been greatly diminished in the modern world, the word and its powerful action will never disappear because God is not going anywhere.

There is a sociological maxim that you must change language before changing a culture. And a shift in worldview is the precursor to the shift in language and culture and all that follows. The pattern could be drawn like this worldview shift → language shift → culture shift → (compassion) policy shift → (compassion) programmatic shift.

The Earl of Shaftesbury wrote

To compassionate, i.e., to join with in passion … To commiserate, i.e., to join with in misery … This in one order of life is right and good; nothing more harmonious; and to be without this, or not to feel this, is unnatural, horrid, immane [monstrous].

In the pre-modern world compassion was a verb (to compassionate). It was the act of journeying with another person in their pain and passion; it was to enter their world, to “walk in their moccasins” – to “join with” another person in their time of difficulty to share with them in their misery – to commiserate.

This understanding of compassion as a verb was rooted in the Biblical narrative, in the nature of God Himself. His name is Compassionate (Exodus 34:5-6). He walked with Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden (Genesis 3:8). He commissioned the building of a tabernacle so he could “dwell among” his people (Exodus 25:8; 29:44-46). God choose to incarnate himself, to live in the midst of his people on earth: “The word became flesh and dwelt among us” (John 1:14). The God of the universe took on the form of a man (Phil 2:7-9). Christ was a faithful high priest, but one who has been tempted as we have (Heb. 4:15). The transcendent Creator of the universe, the fountainhead of compassion, is also the intimate God who acts to compassionate and commiserate with his people.

Jesus want his followers to see compassion as a verb, not a noun.

In the story of the Good Samaritan, we see the something both remarkable and subtle at the same time. An expert in the Jewish law asks Jesus what shall I do to have eternal life (Luke 10:25)? Jesus responds by asking the scholar What does the law say (vs 26)? The lawyer responds correctly that we are to love God and love our neighbor (vs 27). Acknowledging the lawyer’s correct answer, Jesus says, Now go do this! ( vs 28). The lawyer knows he is not doing what the law requires, so to justify himself he asks Jesus And who is my neighbor? (vs 29) Note that the lawyer uses “neighbor” as a noun.

Jesus then tells the story of the good Samaritan (vs 30-35). A priest and a Levite each passed the broken man beside the road and asked, in effect, Is this my neighbor? They had never seen him before, so they concluded they had no obligation to help. Then the Samaritan came. He asked a different question: Is this someone who needs neighboring? The answer was Yes, and Jesus went on to describe the Samaritan’s nine acts of compassion toward the Jew.

Following this description of demonstrating God’s compassion, Jesus asks, Which of these three, do you think, proved to be a neighbor to the man who fell among the robbers?” (vs 36) Note that Jesus changed the word “neighbor” from a noun (who is my neighbor?) to a verb (who acted neighborly?). The lawyer answered: “The one who showed him mercy” (vs 37). Thus the lawyer understood that compassion is an action. Jesus said to him, “You go, and do likewise.”

God’s nature is compassion. He acts compassionately and expects his people to do the same. To be compassionate is to join the person in their need and poverty and to act to help them. To commiserate is to be in such a relationship with the person so as to share in their misery.

This understanding was the definition of compassion in a previous generation when people still acknowledged God’s existence and defined every aspect of their lives in relationship to him. The Webster’s Dictionary of 1834, the American Dictionary of the English Language (the defining dictionary of American’s founding) defined compassion as “A suffering with another; painful sympathy ….” The Oxford English Dictionary (OED) published in 1884 defines compassion as “Suffering together with another, participating in suffering.” Intrinsic to both definitions is being in relationship with someone in their suffering and poverty. It is knowing them and acting compassionately towards them.

Christians of an earlier age demonstrated this. The members of the Clapham Sect in England showed compassion toward women and children working in slave shops, prisoners in English prisons, and black slaves being shipped by the tens of thousands to the shores of the Americas and the plantations in the Caribbean. This group of men and women acted to bring about labor and prison reform and to bring an end to slavery. One of the members of the Clapham Sect and leaders of the abolitionist movement was Zachary Macaulay (1768-1838). In order to experience what the slaves experienced in their journey crossed the Atlantic he booked passage on a slave ship. He personally shared in the slaves misery so that he could better represent his fellow human beings in the fight for their emancipation.

Christians of an earlier age demonstrated this. The members of the Clapham Sect in England showed compassion toward women and children working in slave shops, prisoners in English prisons, and black slaves being shipped by the tens of thousands to the shores of the Americas and the plantations in the Caribbean. This group of men and women acted to bring about labor and prison reform and to bring an end to slavery. One of the members of the Clapham Sect and leaders of the abolitionist movement was Zachary Macaulay (1768-1838). In order to experience what the slaves experienced in their journey crossed the Atlantic he booked passage on a slave ship. He personally shared in the slaves misery so that he could better represent his fellow human beings in the fight for their emancipation.

As a tribute to Macaulay, the commiserater with slaves, his bust was erected in the Westminster Abbey, along with a medallion that conveyed the motto of the abolitionist movement, representing a kneeling slave with the motto ‘Am I not a Man and a Brother?’ The words engraved on the memorial reflect Macaulay’s understanding of the nature of compassion:

As a tribute to Macaulay, the commiserater with slaves, his bust was erected in the Westminster Abbey, along with a medallion that conveyed the motto of the abolitionist movement, representing a kneeling slave with the motto ‘Am I not a Man and a Brother?’ The words engraved on the memorial reflect Macaulay’s understanding of the nature of compassion:

In grateful remembrance of Zachary Macaulay, who, during a protracted life, with an intense but quiet perseverance which no success could relax, no reverse could subdue, no toil, privation, or reproach could daunt, devoted his time, talents, fortune, and all the energies of his mind and body to the service of the most injured and helpless of mankind: and who partook for more than forty successive years, in the counsels and in the labours which guided and blest by God first rescued the British Empire from the guilt of the slave trade; and finally conferred freedom on eight hundred thousand slaves; This tablet is erected by those who drew wisdom from his mind, and a lesson from his life, and who now humbly rejoice in the assurance, that through the Divine Redeemer, the foundation of all his hopes, he shares in the happiness of those who rest from their labours, and whose works do follow them. He was born at Inverary, N.B. [North Britain] on the 2 May 1768: and died in London on the 13 May 1838.

Another example of compassion comes from Nikolaus Ludwig von Zinzendorf1700-1760). As was common during his day, young Zinzendorf, a German Count, made a Grand Tour of Europe -a rite of passage for young aristocrats. At age 19, while in Dusseldorf, the young count viewed Domenico Feti’s painting, Ecce Homo, “Behold the Man.” The painting depicted the crucified Christ. As the bottom of the painting, Feti had written these words from the mouth of Jesus: “This have I done for you – Now what will you do for me?”

Another example of compassion comes from Nikolaus Ludwig von Zinzendorf1700-1760). As was common during his day, young Zinzendorf, a German Count, made a Grand Tour of Europe -a rite of passage for young aristocrats. At age 19, while in Dusseldorf, the young count viewed Domenico Feti’s painting, Ecce Homo, “Behold the Man.” The painting depicted the crucified Christ. As the bottom of the painting, Feti had written these words from the mouth of Jesus: “This have I done for you – Now what will you do for me?”

These words were a knife in young Zinzendorf’s heart, as if Christ were speaking directly to him. From that day he dedicated his life to the service of Christ. In May of 1727 he opened his estate at Hernhut to be a place for the poor and the displaced, an example of com-passion in its fullest sense. Many who came as refugees were Christians and more became Christians. From this group grew an unbroken prayer movement–24 hours a day 365 days a year–that lasted over 100 years. This prayer operation birthed one of the greatest missionary movements in the modern world: the Moravians. Leonard Dober and David Nitschmann, whose story was immortalized in Paris Reed’s sermon, “Ten Shekels and a Shirt,” were two of the missionaries representative of the Moravians. When I first heard this story it moved me to tears. This excerpt is well worth two minutes of your time. Listen and hear how a previous generation understood compassion.

These words were a knife in young Zinzendorf’s heart, as if Christ were speaking directly to him. From that day he dedicated his life to the service of Christ. In May of 1727 he opened his estate at Hernhut to be a place for the poor and the displaced, an example of com-passion in its fullest sense. Many who came as refugees were Christians and more became Christians. From this group grew an unbroken prayer movement–24 hours a day 365 days a year–that lasted over 100 years. This prayer operation birthed one of the greatest missionary movements in the modern world: the Moravians. Leonard Dober and David Nitschmann, whose story was immortalized in Paris Reed’s sermon, “Ten Shekels and a Shirt,” were two of the missionaries representative of the Moravians. When I first heard this story it moved me to tears. This excerpt is well worth two minutes of your time. Listen and hear how a previous generation understood compassion.

The compassionate and commiserative lives of the Moravians inspired William Carey, the father of modern missions, to go to India. It was the Moravians’ example that gave John and Charles Wesley their wholistic vision for preaching the gospel that brought about the social transformation of England.

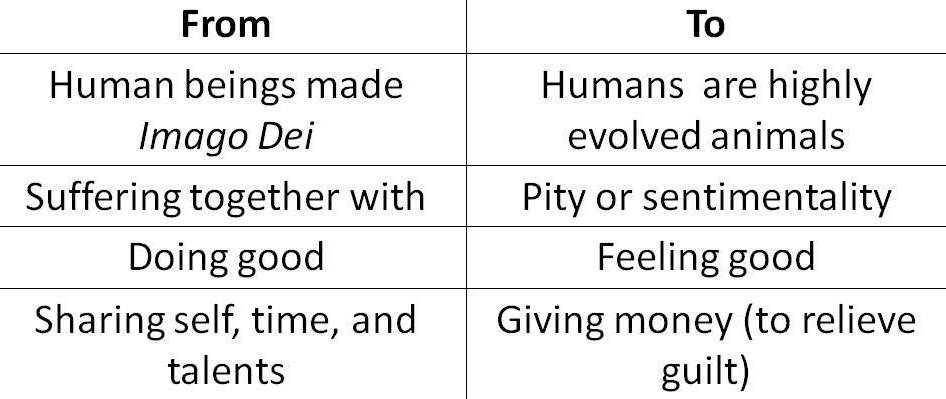

That was then. In the ensuing years our world, and our words, have changed. We have moved from the worship of the Compassionate God, who made people in his own image and who joins with us in our misery, to an atheistic framework in which human beings are animals and only the fittest deserve to survive. In this framework the meaning of the word “compassion” has changed. The Webster’s 2010 New World College Dictionary (online) reflects that change : sorrow for the sufferings or trouble of another or others, accompanied by an urge to help; deep sympathy; pity.

Note the shift in language:

Why has our understanding of compassion shifted? Because our worldview has shifted. Worship is upstream from culture and culture defines our language and our language defines our understanding of compassion. Ideas have consequences! If there is no God in the universe, the concept of compassion is radically changed, might we say deformed.

– Darrow Miller

1 Comment