From part 1 …

The basic worldview assumptions that animated the Civil Rights movement are slowly being replaced by an entirely new set of worldview assumptions. Because of this, race relations have taken a distinctly negative turn, and the gains of previous generations are under threat.

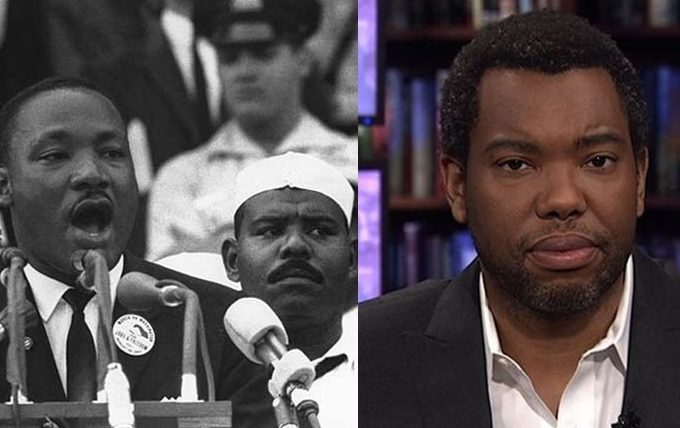

We can see these negative impacts clearly by contrasting two African American leaders: Martin Luther King and Ta-Nehisi Coates. Their view and approaches differ widely.

Justice

Martin Luther King fought for black people to be treated equally, no different than white people, or those of any other ethnicity. His dream was that his children would be treated the same as any other human being—judged by “the content of their character, not the color of their skin.” True justice, for King, must be color blind.

But for Coates, skin color trumps other considerations. He speaks of the “crippling sadness” that he and his son experienced on the day that the grand jury cleared Darren Wilson, the police officer who killed Michael Brown in Ferguson Missouri in 2014. For Coates, it mattered not that the Barak Obama-Eric Holder Justice Department, after an exhaustive inquiry, ruled that the shooting was justified and done in self-defense. For him, the verdict was a self-evident miscarriage of justice. Why? Because Wilson was white and Brown was black.

America

King believed in America. Indeed, King is beloved by all patriotic Americans because of how he helped our nation be evermore true to our founding creed. Consider these powerful words of his “I have a Dream” speech:

Five score years ago, a great American, in whose symbolic shadow we stand today, signed the Emancipation Proclamation. This momentous decree came as a great beacon light of hope to millions of Negro slaves who had been seared in the flames of withering injustice. It came as a joyous daybreak to end the long night of their captivity …

We have come to our nation’s capital to cash a check. When the architects of our republic wrote the magnificent words of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence, they were signing a promissory note to which every American was to fall heir. This note was a promise that all men, yes, black men as well as white men, would be guaranteed the unalienable rights of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness …

I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed: “We hold these truths to be self-evident: that all men are created equal.”

Coates loathes America. For him, the essence of America is slavery, oppression and plunder. He writes, “by erecting a slave society, America created the economic foundation for its great experiment in democracy.” He goes on, “white supremacy is not merely the work of hotheaded demagogues, or a matter of false consciousness, but a force so fundamental to America that it is difficult to imagine the country without it.” (italics added).

In describing America, Coates quotes Lincoln assassin John Wilkes Booth, who said, “this country was formed for the white, not for the black man.” This quote, for Coates, captures the essence of America. There’s no denying the hatred and racism of Booth, or that he represents something larger than himself that has shaped our nation. But here’s the problem with Coates’s writing on America. He spotlights Booth, but ignores Lincoln himself, who wrote: “I am naturally anti-slavery. If slavery is not wrong, nothing is wrong. I cannot remember when I did not so think, and feel.” So what is the character of America? It is the one described by Booth, or by Lincoln? I would argue that you can’t understand America without understanding both, but Lincoln is rightly praised as America’s last founding father—not Booth. Coates, by only focusing on Booth, provides a partial, highly selective (and therefore distorted) picture of America. In doing so, he reveals his postmodern tendency to prioritize narrative at the expense of truth.

In describing America, Coates quotes Lincoln assassin John Wilkes Booth, who said, “this country was formed for the white, not for the black man.” This quote, for Coates, captures the essence of America. There’s no denying the hatred and racism of Booth, or that he represents something larger than himself that has shaped our nation. But here’s the problem with Coates’s writing on America. He spotlights Booth, but ignores Lincoln himself, who wrote: “I am naturally anti-slavery. If slavery is not wrong, nothing is wrong. I cannot remember when I did not so think, and feel.” So what is the character of America? It is the one described by Booth, or by Lincoln? I would argue that you can’t understand America without understanding both, but Lincoln is rightly praised as America’s last founding father—not Booth. Coates, by only focusing on Booth, provides a partial, highly selective (and therefore distorted) picture of America. In doing so, he reveals his postmodern tendency to prioritize narrative at the expense of truth.

Violence

King is famous for advocating non-violence in his fight for civil rights. The title of one of his most famous books says it all: “Strength to Love.” He championed the biblical virtue, “love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you” (Matthew 5:44).

Coates distances himself from King on this issue. He writes disparagingly those who “exult non-violence for the weak and the biggest guns for the strong.” Recalling his father’s Black Panther meetings when he was a boy, he writes, “I was attracted to their guns, because guns seemed honest. The guns seemed to address this country, which invented the streets that secured them with despotic police, in its primary language—violence.”

In an interview with Vox, Coates gives insight into his rather coy view of violence. He is personally against it, but affirming of it at the same time.

When he tries to describe the events that would erase America’s wealth gap, that would see the end of white supremacy, his thoughts flicker to the French Revolution, to the executions and the terror. [He said] “It’s very easy for me to see myself being contemporary with processes that might make for an equal world, more equality, and maybe the complete abolition of race as a construct, and being horrified by the process, maybe even attacking the process. I think these things don’t tend to happen peacefully.”

Civil Rights Agenda

The Civil Rights Movement that King led had a clear agenda: End Jim Crow and bring about a change in America whereby people would be judged not by skin color, but by character. It succeeded overwhelmingly, garnering support from people of all ethnicities. It led to the passage of the famous 1964 Civil Rights legislation, and to the greatest period of equality and harmony between races the nation had ever known.

Coates is very muted about the positive changes that King brought about. He prefers to paint race relations in America circa 2018 as little changed from America in 1850 or 1950. He puts forward no real positive agenda for improved race relations. Rich Lowry comments that his writing “feels nihilistic because there is no positive program to leaven the despair.”

Coates is very muted about the positive changes that King brought about. He prefers to paint race relations in America circa 2018 as little changed from America in 1850 or 1950. He puts forward no real positive agenda for improved race relations. Rich Lowry comments that his writing “feels nihilistic because there is no positive program to leaven the despair.”

He does advocate for reparations. His basic formula goes like this: Take the difference between black and white per capita income, multiply it by the population of blacks, and pay it out each year, for a “decade or two.” This Marxist-style, forced redistribution would amount to somewhere between four and nine trillion dollars, or nearly half of the US GDP. If you are white, you pay, regardless of whether your ancestors were slave owners. If you are black, you receive, regardless of whether your ancestors were slaves. Would such a massive wealth transfer balance the scales of Justice for Coates? No. He writes, “We may find that the country can never fully replay African Americans” (italics added). In other words, his program is one of infinite penance for whites.

Conclusion

Ideas have consequences. King’s ideas, rooted in the biblical worldview, led to many positive results for blacks, and for America as a whole. Coates’s worldview is fundamentally different. It is rooted in a postmodernism that absolutizes group at the expense of the individual. It is rooted in a Marxism that frames reality as a zero-sum contest between powerful oppressors and oppressed victims, and dreams of a world of perfect equality—of outcome, not opportunity. It hungers for vengeance and reparations.

Where will these ideas lead?

If we truly hunger for justice and reconciliation, if we truly want to see race relations in America improve, we must embrace King’s worldview. The most important thing about Coates and King—and about all of us—isn’t our skin color, but our deeply held beliefs and conceptual frameworks. In other words, our worldviews. Ideas have consequences. Only the truth leads to human flourishing. King was far from perfect (as we all are), yet his most famous speeches and writings reflected biblical truth. He modelled reconciliation, forgiveness, and love for all people—even for your enemy. These concepts are lacking from Coates’s worldview.

Tragically, Coates’s worldview is winning out. It is framing the discussion of race in America, not just in the broader culture, but even evangelical leaders are increasingly assuming Coates’s basic worldview framework when speaking on issues of race. If this trend continues, we should not be surprised by even greater hostility, blame-casting, division, and even violence.

- Scott Allen