Cultural relativism asserts that all truth claims are relative to particular cultures or societies. This worldview poses one of the greatest challenges to human flourishing in our generation. As taught in the “soft sciences” of psychology, sociology, and anthropology, it holds that the values in one culture are no better (or worse) than those in another.

But all cultures don’t have the same effects. All cultures are moving either from flourishing to poverty in all its forms, or vice versa.

God created the universe and rested (Gen. 1:31–2:3). Yet creation is unfinished. Why did God stop? As Michael Novak put it in The Spirit of Democratic Capitalism,

Creation left to itself is incomplete, and humans are called to be co-creators with God, bringing forth the potentialities the Creator has hidden. Creation is full of secrets waiting to be discovered, riddles which human intelligence is expected to unlock. The world did not spring from the hand of God as wealthy as man might make it.

From before the creation of the world, God intended man to participate as co-creator or, more accurately, as sub-creator. God creates ex nihilo (out of nothing), we create innovations from the things He has first created. God gave people, His vice-regents, a creation mandate: “Be fruitful and increase in number; fill the earth and subdue it. Rule over the fish in the sea and the birds in the sky and over every living creature that moves on the ground” (Gen. 1:28). Created in God’s image, all people are able to know about their Creator and the laws of creation.

Natural laws, moral laws, development laws

What are these laws? Three primary sets of laws establish the bounds for our lives. Physical or natural laws govern the universe. As we discover and apply them, we take dominion over nature. Moral laws reflect the character of God and provide the blueprint for our moral development. Development laws comprise a cultural framework to guide us in fulfilling the creation mandate to fill and rule the earth. As image-bearers of God, we must discover and apply these laws.

We don’t just discover a precious metal such as gold. We envision all the subsequent uses for that gold. Over time we create those things we have envisioned. Consider lowly sand, which crunches as you walk along a beach and sticks to your feet. But  added to cement and gravel, it makes concrete, which helps us construct awe-inspiring buildings and smooth, useful highways.

added to cement and gravel, it makes concrete, which helps us construct awe-inspiring buildings and smooth, useful highways.

What else can be made with sand? Glass! The windows of our house can keep the weather outside and yet allow daylight in. And silicone, used in the chips that enable us to develop cell phones and computers.

These three sets of laws are inherent in the created order and are universally applicable. Generally, societies that base their civil law on moral law will flourish; those that don’t will wither.

Following God’s laws makes life work better

Intended to benefit man, God’s laws enable individuals and entire cultures to reach God’s purpose for them. As Cecil B. DeMille, the noted twentieth-century film director, said in his commencement address at Brigham Young University in May 1957,

God . . . did not create man and then, as an afterthought, impose upon him a set of arbitrary, irritating, restrictive rules. He made man free—and then gave him the commandments to keep him free. . . . We cannot break the Ten Commandments. We can only break ourselves against them—or else, by keeping them, rise through them to the fullness of freedom under God.

The development ethic encoded in God’s laws is not wishful thinking. Reality affirms it, both historically and practically. The principles embedded in the development ethic lead to human flourishing, even in the face of suffering and persecution. These principles are universal, fixed, eternal, and absolute. While there are no guarantees for material prosperity in every situation in our fallen and sin-scarred world, God’s laws provide the form that makes freedom possible.

These principles, what I call “the development ethic,” expand on Max Weber’s Protestant work ethic. Weber noticed the relative prosperity of European Protestant countries and wondered why. He came to understand that their social ethos created a dynamic that lifted them out of poverty. Weber recognized the awesome power of ideas and ideals, vision and virtue that, when acted on, transformed entire nations. He discerned the interplay of the spiritual with the economic and the political. Creativity and innovation, which come from the minds of women and men, were seen as the source of bounty.

God’s laws are universal, not local

The Reformation established a rationale for everyday life that impacted economic development in the West. In The Spirit of Democratic Capitalism, Michael Novak argues that the application of the Protestant moral philosophy (spirit) to the (democratic) public square and in the marketplace (capitalism) explains the difference in how North and South America developed.

In The West and the Rest, British historian Niall Ferguson argues that those who came from Southern Europe to South America wanted only to plunder the wealth of that great continent, not develop it. The settlers who came from Northern Europe to the “barren shores” of North America, b y contrast, came to transform the land into a place of flourishing through hard work and creative enterprise.

y contrast, came to transform the land into a place of flourishing through hard work and creative enterprise.

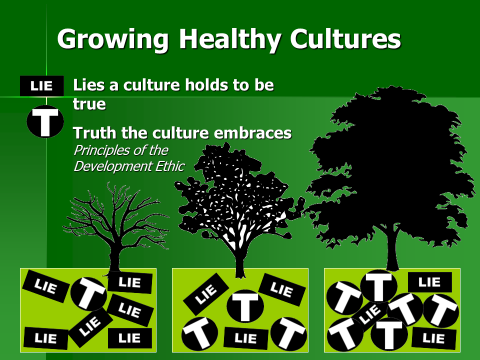

While the development ethic springs from the Scriptures and is best articulated by the Judeo-Christian tradition, it is based on transcendent principles. Of course, the more elements of the development ethic (read, truth) present in a culture, the more readily that society can progress. By contrast, the more lies imbedded in a culture, the less fertile will be the society’s soil for flourishing.

But some cultures develop rapidly with little apparent Judeo-Christian influence. Japan, for example. That’s because these principles don’t belong to Jews and Christians; they govern the creation and bless all humans who discover and apply them. Gravity, for one example, is a universal physical law. It applies to every human, not simply to Christians and Jews.

Live out the development ethic

When it comes to human flourishing, the whole is greater than the sum of its parts. Yet the more elements of the ethic a society has, the more prepared that society is to flourish. Like the strands woven into a piece of cloth, each thread touches the others at different points.

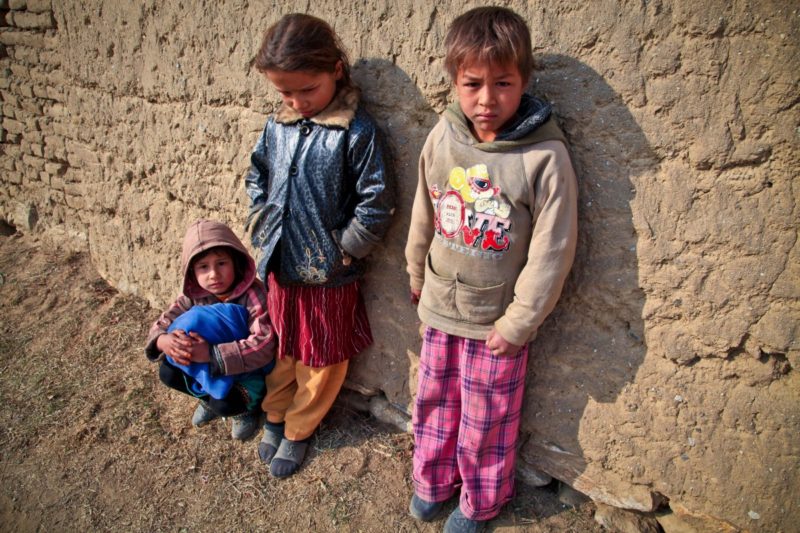

Christians who care about poor and hungry people trapped in the cycle of poverty must articulate the development ethic and share its values and ideals with them. Our task is not to impose a set of values, however. We are never to think of this gentle process as “civilizing the savages.” The late Chuck Colson once articulated the spirit in which we must share this ethic: “The Christian Church makes a Great Proposal, inviting everyone to the table, regardless of color, ethnic origin, background, or economic status. We’re inviting people to consider a worldview that works, that makes sense, through which people can discover shalom and human flourishing.”

Christians who care about poor and hungry people trapped in the cycle of poverty must articulate the development ethic and share its values and ideals with them. Our task is not to impose a set of values, however. We are never to think of this gentle process as “civilizing the savages.” The late Chuck Colson once articulated the spirit in which we must share this ethic: “The Christian Church makes a Great Proposal, inviting everyone to the table, regardless of color, ethnic origin, background, or economic status. We’re inviting people to consider a worldview that works, that makes sense, through which people can discover shalom and human flourishing.”

Sharing this ethic gives the poor an alternative, a way out. Then they must choose whether to flourish or to perish, to embrace life or death. Ultimately, the encouragement of human flourishing involves discipling both individuals and cultures, founded on the creative and redemptive work of God and His story.

- Darrow Miller

This DM&F Classic blog post is excerpted from the book Discipling Nations. For the entire text go here.