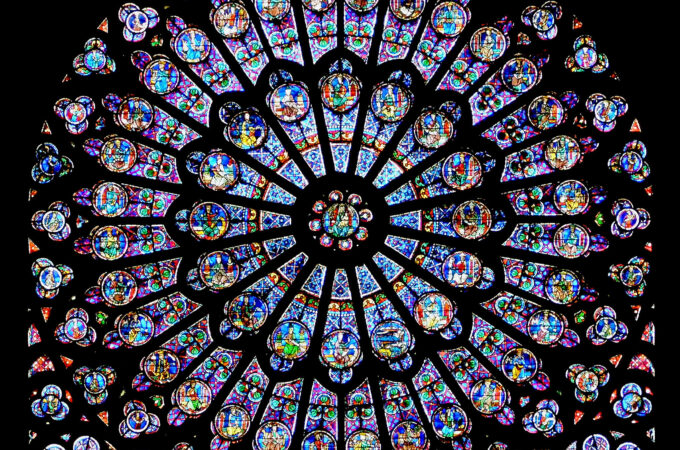

Krzysztof Mizera creates art in a stained-glass window – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=7768903

Daniel Borstein was director of the United States Library of Congress. He wrote a book about human creativity and the arts entitled The Creators which he begins with a question: Where did the impulse for art come from?

Everywhere in the world, people have a compulsion to express themselves through the arts and music. Every culture has its artists, and every religion has adherents who are artists. Why? What’s the impulse for this? Borstein wanted to find out.

He studied Hinduism, and concluded it conveys no impulse for art. Hinduism affirms no creation, only decreation, the fragmentation of the One.

He considered Confucianism, not a religion so much as a philosophy. Confucius was not interested in origins; he thought everything came about as a natural process, similar to evolution. For him, there was no God, just nature. Confucius attributed everything in the creation to a process of natural forces.

As for Buddhism, Borstein concluded the Buddha didn’t know whether or not a creator existed, but if he did, he was prepared to extinguish himself; the Buddha aimed at uncreation. The lord of the Buddhist was the master of extinction, which leaves no model for man as a creator at any level.

The Greeks saw creation as an act of procreation by the gods. Polytheists, the Greeks regarded gods as simple but larger-than-life humans, not transcendent. Every act of creation was an episode of divine love or hate; the gods had intercourse and birthed Greek heroes.

Borstein studied Islam, which, like Judaism and Christianity, affirms a beginning, but Allah was more an orderer of facts, a commander of life and death. The god of Islam is arbitrary, with a focus on power and authority.

The impulse for art comes from one Source

Secularism lacks any transcendence; it strips the universe of a creator. As with Confucianism, the world is simply material, life came into being somehow. Humans are machines, without souls or spirits, merely products of electrical and chemical impulses. This leaves no place for a creative impulse.

Borstein writes 80 pages surveying all these religions and philosophies and finds no impulse for art. He’s stuck with the question, Where does the impulse for art come from?

Until he reads something from a well-known book: “In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth.” Whoa!

Every philosophy and religion has artists, but not because these thought systems gave rise to artists; they didn’t and they don’t. Artists exist everywhere because they are made in the image of God, the First Artist, and that’s where the impulse for art comes from.

God existed before the physical universe. He fashioned the creation out of nothing. He imagined it and created it. God is the primary creator, humans, made in His image, are secondary creators. We can act upon what He has made.

This truth should lead us to worship. We have a great and beautiful God who does everything perfectly for a defined purpose. He gave us minds to discover, spirits to explore, to ask questions. God has hidden things He wants people to discover. Imagine how much remains which He has concealed for us to uncover! How much music is yet to be scored, how many poems to be written, canvases awaiting the painter’s brush? Think of all the beauty and wonder yet to move from a heart into the artistic realm where it might be shared.

Throughout much of history, Christians had a biblical theology of beauty and creativity. They produced some of the most beautiful art: paintings, music, prose, poetry, hymns, sculptures, architecture, stained glass, etc. This was because Christians understood that God is gloriously beautiful, and has placed in His imago Dei creature the impulse for creative expression.

Sadly, much of the church today is framed by the sacred/secular divide, the separation of the spiritual from the physical. The theology of beauty has been replaced with a theology of utility. Art is unspiritual unless it is religious or used in worship or evangelism. In much of the church today there is little place for the arts, little support of artists to depict the glory of God and thereby edify the community.

We need to follow the psalmist’s imperative, “Oh, worship the LORD in the beauty of holiness! Tremble before Him, all the earth.” Psalm 96:9 NKJV

Beauty and truth converge

Beauty and truth converge

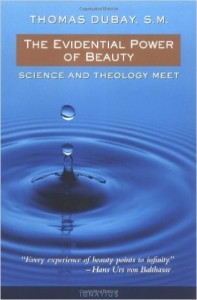

Roman Catholic theologian Thomas Dubay wrote The Evidential Power of Beauty, the most profound book I have ever read on the subject. He points out that appreciation for beauty requires humility. Are you humble enough to sit and look at a dandelion? We like to look at roses, but are we humble enough to look at a dandelion?

Some of Dubay’s most compelling observations lie in two chapters devoted to scientists—and not just Christian scientists—speaking about beauty. Many of these highly educated and brilliant professionals—scientists, mathematicians, astronomers, and physicists—are professing atheists who spend their whole lives working to solve an elusive problem. Dubay records a fascinating experience common to many of these experts: when they see beauty they know they’re nearing the end of their quest. After weeks, months or even years of unraveling complex puzzles, as they approach the solution, beauty emerges in front of them. Beauty becomes a marker of truth!

And, of course, that comports with reality. God is beautiful and He is true. When you see beauty, you are witnessing truth implanted in the creation by God.

We see this all over the creation, at the micro level as well as the macro level. Consider Isaiah’s words, for example:

“To whom will you compare me? Or who is my equal?” says the Holy One. Lift your eyes and look to the heavens: Who created all these? He who brings out the starry host one by one, and calls them each by name. Because of his great power and mighty strength, not one of them is missing. (Isaiah 40:25-26 NIV)

Not one of them is missing? One of how many?

Not one star is missing

Scientists believe the universe contains at least 2 trillion galaxies, each containing billions of stars, totaling “at least 70 septillion” stars in the universe. (Here’s another way to depict this vastness: they also believe there are at least 10,000 stars for every grain of sand on Earth.)

Of 70 septillion stars, not one is missing.

If someone dumped just one cubic foot of sand on your kitchen floor, a mere one billion grains, could you keep track of every grain? Would you know if any were missing?

Behold the glory and majesty and beauty of our God. Let us worship him.

- Darrow Miller