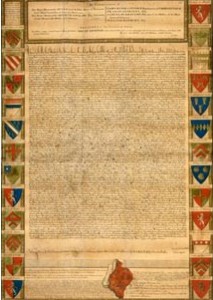

British historian and author Philip Quenby has just finished a five-part documentary to celebrate the 800th anniversary of Magna Carta. The series examines Magna Carta and its legacy in politics, science, society, law and warfare. “Magna Carta Unlocked” can be streamed here.

British historian and author Philip Quenby has just finished a five-part documentary to celebrate the 800th anniversary of Magna Carta. The series examines Magna Carta and its legacy in politics, science, society, law and warfare. “Magna Carta Unlocked” can be streamed here.

Quenby argues that the development of modern civil liberties on the back of Magna Carta taps deeply into the biblical concept of man made in the image of God, man with free volition, man free to choose to accept Christ or to deny Christ. He argues that Magna Carta self-consciously drew on Saxon legal codes and customs which were rooted in the Old Testament teaching of the 10 Commandments. In the article “Magna Carta: A Text for Our Time” (which appears on the Sceptred Isle website referred to above) we find these words:

This was of profound importance for two reasons in particular. Firstly, Saxon legal codes made it clear that kings were subject to the law: by placing the ruler under the same constraints as everyone else, Saxon law carried within itself the promise of rights for the common man and thus not only the seed of what Magna Carta eventually grew to become, but also the germ of democracy itself. Rights for the common man because, if a king was subject to the law, the corollary was that a subject could rely on that same law to protect him in his dealings with the state, so the subject had rights which the state could not override. And the germ of democracy because, as time passed, it became increasingly difficult to deny political rights to subjects who had legal rights – equality in one arguing strongly for equality in the other.

Secondly, the laws of King Alfred began by reciting the Ten Commandments and various other Old Testament laws. By putting God’s law first and man’s law second, they recognised that law is not simply what we choose to make it, but is answerable to a higher moral standard based on and derived from the Bible.

Limits on state power and a corresponding freedom for individuals from arbitrary or excessive use of that power were thus part of English heritage almost from the start, deriving from a mixture of Saxon customs and biblical teaching. That is not to say that the liberties now associated with Magna Carta sprang fully formed into the light: far from it – many were initially present only in the most shadowy form and needed to be developed through a process that was often painful and almost always contentious. The meaning and relevance of the Great Charter was fought over in the English Civil Wars of the 1640s, for example, when the supporters of Parliament specifically relied on it to justify their armed rebellion, but elements of it remained in issue for centuries afterwards. The very existence of a right to free speech was uncertain as late as the reign of Charles II, whose Licensing Act of 1662 prohibited the publishing of any work without government approval, whilst freedom of conscience was to prove a thorny problem for generations afterwards.

Limits on state power and a corresponding freedom for individuals from arbitrary or excessive use of that power were thus part of English heritage almost from the start, deriving from a mixture of Saxon customs and biblical teaching. That is not to say that the liberties now associated with Magna Carta sprang fully formed into the light: far from it – many were initially present only in the most shadowy form and needed to be developed through a process that was often painful and almost always contentious. The meaning and relevance of the Great Charter was fought over in the English Civil Wars of the 1640s, for example, when the supporters of Parliament specifically relied on it to justify their armed rebellion, but elements of it remained in issue for centuries afterwards. The very existence of a right to free speech was uncertain as late as the reign of Charles II, whose Licensing Act of 1662 prohibited the publishing of any work without government approval, whilst freedom of conscience was to prove a thorny problem for generations afterwards.

The point, however, is that (whatever might be said on the other side of the equation) in England there was always a strong impetus towards freedom – strong enough almost to be called a moral imperative – by virtue of the way that the influence of the Bible was rooted not only in Magna Carta but in the law and in ideas of kingship.

From the moment it was granted, Magna Carta held out the promise of freedom – freedom from arbitrary rule, freedom from oppression, freedom from tyranny. That was the clear implication of clause 39, which spoke of no free man being imprisoned except by the judgment of his peers or due process of law. Those provisions in their turn opened the door to other freedoms such as freedom of conscience, for what greater tyranny could there be than trying to dictate what men and women should think, of seeking to rule the inner life as well as the outer? As soon as the Great Charter set about curtailing arbitrary or disproportionate exercise of royal power, the logic of a society which was not only formed by Christian values but had these embedded at the very heart of its laws and as a central determinant of the relationship between citizen and state made a compelling case for the charter’s original liberties to be extended and then extended again. Arguments in favour of freedom of conscience, for example, drew heavily on the fact that choice was of the essence of Christianity – the freedom to accept Christ or reject him – so that it simply made no sense to try and compel what had to be freely given; and this outlook in turn reinforced the tendency towards freedom, since choice is the enemy of dictatorship. Likewise, Christian belief in free will reinforced ideas of freedom of the individual.

For more see Magna Carta: A Text For Our Time?

Here’s an interview of British historian Philip Quenby discussing highlights of the series Magna Carta Unlocked. (Note: Don’t watch this unless you’re prepared to be persuaded to see the series!)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=N4Uoz-nLs3g&feature=youtu.be

Be sure to visit Sceptred Isle Productions. Any energies you give to learning about this project will be well spent.

- Darrow Miller