What’s driving today’s polarization around race? And what’s the answer?

Two opposite answers—two narratives, if you will—are unfolding. One emphasizes systemic injustice and institutional racism. It views the problems black people face as sourced outside their community and attributes these problems to historic slavery and pervasive, systemic white oppression.

The other narrative emphasizes the importance of personal responsibility; evil is rooted in human hearts. Yes, white racism persists, but much bigger challenges confront the black community, challenges that can be overcome by the actions and decisions of black people in ways that are not ultimately dependent on the actions of white people.

Here’s the latest in our current series, A Dialogue on Racism and Christian Racial Reconciliation.

~

Dear Andrew and Dennae,

I’m impressed by the time and care you’ve put into your responses, and am sincerely grateful for the opportunity to clarify issues and sharpen my thinking. I share your deep passion and commitment to biblical justice, and your desire to be a voice for the voiceless and to uphold the cause of the poor and the oppressed.

While I’ve developed strong convictions on these topics, I have much to learn and undoubtedly have unbiblical perspectives that need correcting. For this reason, I value your friendship. I’m very aware of my shortcomings. I have logs in my eyes that need to be removed. I need your help seeing them. I also want to be the kind of person who loves others enough to help them remove the logs from their eyes as well. This is my heart.

I’d like to begin with what I believe is the most important part of your last post, your strong affirmation of critical social theory. You wrote:

- “[C]ritical theories have been incalculably important for the re-education of America.”

- “While we would disagree with aspects of various sociological work, we view the discipline [critical social theory] as a whole as a partner in the call for sweeping reforms.”

- “[C]ritical theories are a form of common grace …”

- There is “commonality between critical theories and Christian ethics.”

In my previous post, I noted that critical social theory is rooted in atheistic philosophy. You wrote that this was “not germane” and essentially not relevant to a Christian consideration of the importance of this ideology to racial reconciliation.

I applaud your clarity here. You state unambiguously that when addressing the topic of racial reconciliation, critical social theory is an “incalculably” important asset to supplement the teachings of Scripture.

On this point, however, we are in disagreement. My own analysis has led me to conclude the opposite. I’ll devote much of my response to explaining why I’ve come to this conclusion. In short, I view critical social theory as a destructive ideology that rends the social fabric and exacerbates racial tension. Over the past five years, I’ve become increasingly alarmed by its massive influence in the broader culture, and within the evangelical church in particular.

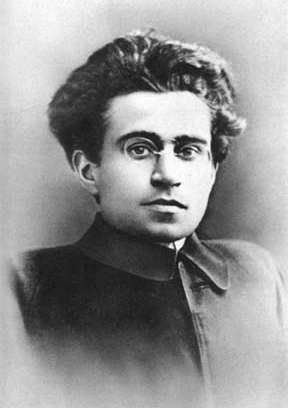

I believe that to rightly comprehend critical social theory, you have to see it as much more than a set of ideas that relate to power, race, sex, and sexual orientation. You have to see it as a comprehensive worldview. Many now describe it as a kind of religion. It provides answers to all the big worldview questions: What is ultimately real? What does it mean to be human? What is wrong with the world and how can it be made right? And many more. Its answers differ sharply from those provided by a biblical worldview, which isn’t surprising when you consider that the source of this worldview is a European philosophical tradition known as Idealism and the writings of philosophers such as Kant, Hagel, Nietzsche, and Rousseau. From this philosophical soil both Marxism and postmodernism emerged, with people like Antonio Gramsci, Sigmund Freud, Michel Foucault, and Jacques Derrida making contributions along the way. It gave rise to the Frankfurt School social theorists, who first coined the phrase “critical theory.” These people, including Herbert Marcuse (the father of the sexual revolution) and Max Horkheimer, brought their ideas into American universities in the 1950s where they eventually came to dominate the social sciences and humanities, and ultimately large swaths of the culture in our own time. These ideas were picked up and developed by Derrick Bell, father of critical race theory, whose ideas inspired present-day popularizers including Richard Delgado, Kimberlé Crenshaw, Ibram X. Kendi, Robin DiAngelo, and the founders of Black Lives Matter, to name a few.

I believe that to rightly comprehend critical social theory, you have to see it as much more than a set of ideas that relate to power, race, sex, and sexual orientation. You have to see it as a comprehensive worldview. Many now describe it as a kind of religion. It provides answers to all the big worldview questions: What is ultimately real? What does it mean to be human? What is wrong with the world and how can it be made right? And many more. Its answers differ sharply from those provided by a biblical worldview, which isn’t surprising when you consider that the source of this worldview is a European philosophical tradition known as Idealism and the writings of philosophers such as Kant, Hagel, Nietzsche, and Rousseau. From this philosophical soil both Marxism and postmodernism emerged, with people like Antonio Gramsci, Sigmund Freud, Michel Foucault, and Jacques Derrida making contributions along the way. It gave rise to the Frankfurt School social theorists, who first coined the phrase “critical theory.” These people, including Herbert Marcuse (the father of the sexual revolution) and Max Horkheimer, brought their ideas into American universities in the 1950s where they eventually came to dominate the social sciences and humanities, and ultimately large swaths of the culture in our own time. These ideas were picked up and developed by Derrick Bell, father of critical race theory, whose ideas inspired present-day popularizers including Richard Delgado, Kimberlé Crenshaw, Ibram X. Kendi, Robin DiAngelo, and the founders of Black Lives Matter, to name a few.

As regards Christian mission, I see critical social theory not as a partner, but as a competitor. I fully agree with Christian apologist Neil Shenvi, who wrote: “I worry that too many people are trying to hold on to both Christianity and critical theory. That’s not going to work in the long run. Either we will abandon historic Christianity in favor of the core tenets of contemporary critical theory or we will abandon the core tenets of contemporary critical theory in favor of Christianity. Any amalgamation of the two will, in the long run, be unstable.” In short, I view critical social theory as a “hollow and deceptive philosophy, which depends on human tradition and the elemental spiritual forces of this world rather than on Christ” (Colossians 2:8).

In your previous post, you wrote that I “demonstrate no genuine engagement with any particular critical theories or theorists.” While I certainly make no claim to be an expert, I have tried to understand this ideology as best I can. Over the past five years, I have undertaken a fairly extensive study, reading from original sources, including the most influential popularizers like DiAngelo and Ta-Nehesi Coates. I’ve also read the books of evangelical proponents of critical race theory, including Ken Wytsma, Eric Mason, and Latasha Morrison. I’ve also read the critics of critical theory, both Christian and non-Christian, including James Lindsay, Neil Shenvi, and Thaddeus Williams. I’ve discovered that some of the clearest and most forceful critics are black academics like Shelby Steele, Glenn Loury, Thomas Sowell, and John McWhorter, and black evangelicals  like Robert Woodson, Darrell Harrison, Virgil Walker, Chantal Monique Duson, Voddie Baucham, and Ryan Bomberger. I’ve learned a great deal from each of them.

like Robert Woodson, Darrell Harrison, Virgil Walker, Chantal Monique Duson, Voddie Baucham, and Ryan Bomberger. I’ve learned a great deal from each of them.

I’d like to share my attempt at summarizing the basic worldview presuppositions of critical social theory, showing how they differ from biblical presuppositions. I encourage readers of this exchange to do their own research and decide if they think my summary is fair or not.

Last week, Tim Keller published the most recent article in his series on race: “A Biblical Critique of Secular Justice and Critical Theory.” I deeply appreciated his analysis of what he calls “postmodern critical theory,” which, he asserts, “draws on the teachings of Karl Marx.” It closely tracks my own thinking. I know you both respect Keller, so I’ll quote from his article extensively.

Andrew and Dennae, as you read this summary below, please know that I’m not suggesting that you agree with or support all of these presuppositions. I’m sure you don’t. You said in your previous post that you “disagree with aspects of various sociological work, yet we view the discipline as a whole as a partner in the call for sweeping reforms.” You also said that “the kingdom of God … calls us to make substantive critiques of all ideologies.”

This is simply my attempt to summarize the core, or “least common denominator” of critical theory and contrast it with core biblical beliefs. I’m quite certain that you’ll view this summary as overly simplistic and unhelpful. Perhaps in your final post you can explain how you feel I’ve missed the mark, and which aspects of critical social theory you find helpful and which parts you don’t.

Ultimate Reality

Because critical theory is grounded in atheism, there is no God, no objective truth, and no transcendent morality. All that remains is power, and in particular, an endless struggle for power between various groups. This explains why critical theory, at its core, is concerned with power: Who has it, who doesn’t, and how those who have it establish systems, structures, and norms to maintain it and to dominate and subjugate those who don’t. Power, in this framework, is entirely negative and zero-sum; the world is divided into an oppressor-oppressed binary, with nothing existing outside these categories.

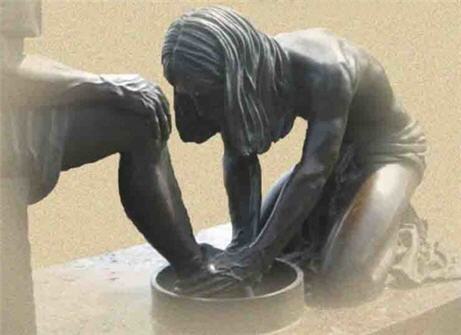

As I said in my last post, there is a degree of truth in this analysis. The Bible agrees that power typically functions this way in our fallen world. Jesus said to his disciples in Mark 10:43, “You know that those regarded as rulers of the Gentiles lord it over them, and their superiors exercise authority over them.” But then He pivots, contrasting power and authority in the fallen world with power in God’s Kingdom:

But it shall not be this way among you. Instead, whoever wants to become great [that is, whoever wants to possess power and authority] among you must be your servant, and whoever wants to be first must be the slave of all. For even the Son of Man [the most powerful being in the universe, the supreme authority] did not come to be served, but to serve, and to give His life as a ransom for many.

But it shall not be this way among you. Instead, whoever wants to become great [that is, whoever wants to possess power and authority] among you must be your servant, and whoever wants to be first must be the slave of all. For even the Son of Man [the most powerful being in the universe, the supreme authority] did not come to be served, but to serve, and to give His life as a ransom for many.

Power is not all that exists. Everything cannot be reduced to power. God exists. He has all power and authority (Matthew 28:18), yet, in love, He uses His power to serve those under authority. Those who follow His example bring this revolutionary approach to power and authority into the fallen world, and in doing so, transform it. Power exists, but so does truth, and so does love. And because love exists at the foundation of reality, so does grace, mercy, and forgiveness.

These redemptive qualities are completely foreign to critical social theory. In the zero-sum world of social justice power struggle, there is no “live and let live” tolerance. No win-win, or even compromise. No place for forgiveness, or grace. No “love your enemy.” No “first get the log out of your own eye” introspection. There is only grievance, condemnation, and retribution. Bigots, haters, and oppressors must be destroyed. We are seeing this happen with alarming frequency in what is now called “cancel culture,” which is a bitter fruit of critical theory.

Here is Keller on this topic:

- [In postmodern critical theory] “reality is at bottom nothing but power.”

- “Religious doctrine, together with all politics and law are always, at bottom, a way for people to get or maintain … power over others.”

- “Power structures mask themselves behind the language of rationality and truth. So academia hides its unjust structures behind talk of ‘academic freedom,’ and corporations behind talk of ‘free enterprise,’ science behind talk of ‘empirical objectivity’, and religion behind talk of ‘divine truth’. All of these … are really just constructed narratives designed to dominate…”

Keller highlights the futility of this cynical view of reality: “… if all people with power … inevitably use it for domination, then if any revolutionaries were able to replace the oppressors at the top of the society, why would they not become people that should subsequently be rebelled against and replaced themselves? What would make them different?”

Good questions.

Keller then contrasts the critical theory view of power with the biblical view.

Rule and authority [that is, power] are not intrinsically wrong. Indeed, they are necessary in any society. But while not ending the [ruler/ruled] binary, neither does Christianity simply reverse it. It does not merely fill the top rungs of authority with new parties who will use power in the same oppressive way that is the way of the world… Because it is rooted in the death and resurrection of Jesus, Christianity neither eliminates nor merely reverses the ruler/ruled binary—rather, it subverts it. When Jesus saves us through his use of power only for service, he changes our attitude toward and our use of power.

… to be continued