What’s driving today’s polarization around race? And what’s the answer?

Two opposite answers—two narratives, if you will—are unfolding. One emphasizes systemic injustice and institutional racism. It views the problems black people face as sourced outside their community and attributes these problems to historic slavery and pervasive, systemic white oppression.

The other narrative emphasizes the importance of personal responsibility; evil is rooted in human hearts. Yes, white racism persists, but much bigger challenges confront the black community, challenges that can be overcome by the actions and decisions of black people in ways that are not ultimately dependent on the actions of white people.

Here’s the latest in our current series, A Dialogue on Racism and Christian Racial Reconciliation

~

[This is part 4 of Scott’s response, following part 1, part 2, and part 3.]

Fundamentalism

You wrote:

We view most Evangelical criticism of critical theory and BLM [Black Lives Matter] as the same Fundamentalism of a century ago… American Fundamentalism is the main force that has perpetuated segregation to this day, and it is the same force currently trying to silence the cries for reform. We pray daily that this Fundamentalism fails.

I agree that there are striking parallels between our situation today and the church split some 100 years ago between the mainstream denominations and the fundamentalists. I wrote about this in a WORLD article (“History repeats itself”). I hope you’ll take the time to read it. I do not disparage people like J. Gresham Machen, or  R.A. Torrey, founder of Biola University. They were not perfect, and their overreaction to the social gospel caused real harm to the church. But to their everlasting credit, they stood firm and preserved the gospel in their generation, while the mainstream churches largely abandoned it in their tragic attempt to accommodate the powerful, unbiblical ideologies of their day. Had they not done this, the church in America today would look a lot more like the nearly extinct church in Western Europe.

R.A. Torrey, founder of Biola University. They were not perfect, and their overreaction to the social gospel caused real harm to the church. But to their everlasting credit, they stood firm and preserved the gospel in their generation, while the mainstream churches largely abandoned it in their tragic attempt to accommodate the powerful, unbiblical ideologies of their day. Had they not done this, the church in America today would look a lot more like the nearly extinct church in Western Europe.

Then, and now, the church isn’t supposed to blindly follow mainstream cultural trends—even powerful ones with massive elite support and financial backing, like Black Lives Matter, whose founders and leaders openly advocate for their neo-Marxism and postmodern critical theory. Our call is to uphold and live out the counter-cultural ways of Christ’s kingdom as salt and light in the midst of an increasingly dark and chaotic culture.

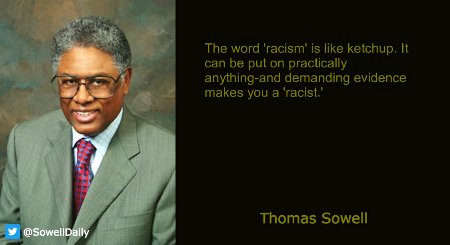

“Who is [sic] your people? Who are you? Is it shibboleth or sibboleth?”

I’m not sure what you are asking here, or why. In my previous post, I mentioned that the phrase “systemic racism” is now so overused, that even those who invoke it struggle to define it. It has become more of a catch-phrase or password (a shibboleth) that people use to signal that they are part of the in-crowd. This is not to say that systemic evil  and injustice are not real. They are. But they are not nearly so vague and undefined as people are making them out to be. I’ll be the first to stand with you against systemic racism, but I first need to be pretty certain that a system is racist, and that means evidence that goes beyond disparities of outcome and that takes into account personal choices and behaviors. Proclaiming a system to be racist when it isn’t is unjust and makes things worse. It leaves root problems unaddressed.

and injustice are not real. They are. But they are not nearly so vague and undefined as people are making them out to be. I’ll be the first to stand with you against systemic racism, but I first need to be pretty certain that a system is racist, and that means evidence that goes beyond disparities of outcome and that takes into account personal choices and behaviors. Proclaiming a system to be racist when it isn’t is unjust and makes things worse. It leaves root problems unaddressed.

Who am I? Who are my people? I’m not sure why you are asking these questions, but here’s my straightforward answer. Who am I? First and foremost, I’m a child of God, a sinner saved by grace, and a follower of Jesus Christ. I have a unique history, personality, and gifts which I’m grateful for. I’m a proud American. I have a particular calling and vocation which gives great meaning and purpose to my life. Who are my people? First and foremost, my wife and five children, my mom and dad, and my sister, brother, grandparents, and in-laws. Second, my brothers and sisters in Christ, including both of you, and in particular, my DNA coworkers and colleagues around the world, and those at our home church whom I know on a very personal level. Third, my fellow Americans. These are my people. “White” doesn’t factor into my answer, because my people include those with every skin hue and color.

What does racial reconciliation look like?

You asked, “what does racial reconciliation look like for White Evangelicals? How do you define ‘racial reconciliation’ and what practically would you suggest pastors do to engage their congregations in this work?”

Thank you for asking this very important set of questions. First, I would never presume to speak for a group as varied and amorphous as “White Evangelicals.” Second, I define racial reconciliation as building or re-establishing a culture of trust and love between different racial/ethnic groups where that trust has eroded or broken, and where distrust, enmity and hostility exists.

There are many precious Biblical truths that foster racial reconciliation. These truths have to be taught by faithful pastors and ministers of reconciliation. They include:

- There is only one race, the human race, and all of us are brothers and sisters with the same blood in our veins, and the same ancestors.

- We share a common human nature. We are all created by God in His Divine image and likeness. We are all objects of His love. All people, regardless of ethnicity, skin color, sex, religion, or class possess inherent and incalculable value and worth, along with God-given rights to life and liberty.

- We are all sinners. All of us are more than capable of the most heinous evil. There is no group or ethnicity that is more evil than another. We all stand in need of God’s grace and forgiveness, which He freely offers to all people regardless of ethnicity or skin color.

- To those that accept Christ’s mercy and forgiveness, they become part of the same family, the children of God, where there “is neither Jew nor Gentile, neither slave nor free, nor is there male and female, [or black or white], for you are all one in Christ Jesus” (Galatians 3:28).

These truths provide the only solid foundation for genuine racial reconciliation that I know of.

Postmodern critical theory denies each of these truths. You won’t find them anywhere in DiAngelo’s White Fragility, or Kendi’s How to Be an Antiracist. Instead, critical theory reduces people to impersonal representatives of social groups based on skin color, sex, or sexual orientation. It then pits them against one another without any element of mercy or forgiveness. Keller is exactly right: “It makes forgiveness, peace, and reconciliation between groups impossible.”

Another key to racial reconciliation is truth. Mistrust and hostility grow in cultures where truth is eroded and replaced by lies, false witness, and false narratives. For example, we regularly hear that the police are killers who have declared “open season” on young black men. Black Lives Matter leaders routinely repeat this line. This isn’t so much an exaggeration as an outright lie. It only exacerbates mistrust and hostility. That hostility will continue unless the truth can overcome the lie. Christians ought to be people of truth who refuse to traffic in inflamed or hyperbolic charges that aren’t grounded in solid evidence and fact, but only serve to buttress a particular narrative.

Another key is to treat people as unique individuals, and not to dehumanize them as avatars or representatives of groups based on skin color. In King’s immortal words: “I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin, but by the content of their character.” This statement represented the high-water mark in American race relations because Americans of all skin colors overwhelmingly agreed with him! They said with one, loud voice, “Yes, this is the kind of America we want to live in too!”

Tragically, postmodern critical theory has abandoned this dream and moved us backward. Now, skin color is all-important, and the individual person, including the content of their character, no longer counts for much. This isn’t progressing, it’s regressing. If we want genuine racial reconciliation, we have to reclaim and affirm King’s great dream in our generation.

Finally, and as part of the above, we need to hold people accountable for their own sins, and not for the sins of people who lived over a hundred years ago who happen to share their same skin color. You wrote: “the great hope and joy for countless Christian leaders in this season is that repentance leads to reconciliation and restoration, and the Black community is still offering us this reconciliation.”

By “us” I assume you mean people with white skin. But do you truly believe that merely based on your skin color, you are morally guilty and need to repent for sins committed by people with the same skin color who may have lived centuries ago? And that if you have black skin, you are, on that basis alone, sinned-against by white people?

Assuming a person is morally guilty or innocent of sin on the basis of their skin color alone, and not because of their individual actions and behaviors may be true for postmodern critical theory, but it is unbiblical and unjust. This mindset can only exacerbate racial hostility. Repentance for sin is a hugely important matter. I daily have to repent, but I repent for and am accountable for my sins. Not my parent’s sins (Ezekiel 18:20), let alone the sins of complete strangers, simply because we have the same skin color.

Last point: I’m impressed with this article by George Yancey. He presents many helpful suggestions for improving race relations that I would endorse.

I’ve gone on far too long. Forgive me. Like you, I have real passion for this issue and get carried away. I count you both as friends, and my great wish for you both is that your lives, families, and ministries will thrive and bear great fruit for God’s Kingdom. God bless you both. I look forward to reading your final installment.

In Christ,

Scott