It has been said that cultures build systems of charity in the image of the God they worship. In other words, the foundational belief systems of a society will inevitably determine the culture of that society, which, in turn, will shape its institutions and programs—including those dedicated to poverty fighting.

In examining American history from the early colonial period through the mid-1800s, it becomes apparent that the God they worshipped was, for the most part, the God of the bible, and particularly, the Protestant understanding of that God. In fact, early American efforts at poverty fighting have been referred to as “Social Calvinism” by some observers. The poverty fighting systems of Social Calvinism were based on foundational principles about the nature of God, man, and creation as understood from Scripture.

Hard headed and warm hearted

In the young America, the emphasis was on a God of both justice and mercy. This balance led to an understanding of compassion that was both hardheaded but warm hearted. Since justice meant punishment for wrongdoing, it was right for the slothful to suffer. And since mercy meant rapid response when people turned away from past sins, neglect of those willing to shape up was also wrong. Secondly, there was emphasis on man’s unlimited potential for goodness as God’s image-bearer, but also on his sinfulness and depravity due to his “fallen” state of separation from God. Poverty was rooted in this very separation. As a result, the only final hope for the elimination of poverty came through an internal heart and mind transformation on the part of the individual. Since God’s law overarched every aspect of life, the most important need of the poor who were unfaithful was to learn about God and God’s expectations for man. Through passages such as 2 Corinthians 8:9 (“You know the grace of our Lord Jesus Christ, that though he was rich, yet for your sakes he became poor, so that you, through his poverty, might become rich.”) early American poverty fighters clearly understood that it was only though God’s grace that the poor could become rich.

In the young America, the emphasis was on a God of both justice and mercy. This balance led to an understanding of compassion that was both hardheaded but warm hearted. Since justice meant punishment for wrongdoing, it was right for the slothful to suffer. And since mercy meant rapid response when people turned away from past sins, neglect of those willing to shape up was also wrong. Secondly, there was emphasis on man’s unlimited potential for goodness as God’s image-bearer, but also on his sinfulness and depravity due to his “fallen” state of separation from God. Poverty was rooted in this very separation. As a result, the only final hope for the elimination of poverty came through an internal heart and mind transformation on the part of the individual. Since God’s law overarched every aspect of life, the most important need of the poor who were unfaithful was to learn about God and God’s expectations for man. Through passages such as 2 Corinthians 8:9 (“You know the grace of our Lord Jesus Christ, that though he was rich, yet for your sakes he became poor, so that you, through his poverty, might become rich.”) early American poverty fighters clearly understood that it was only though God’s grace that the poor could become rich.

Worthy of relief

This emphasis on the individual need of conversion led early poverty fighters to the conviction that was more important to know the poor individually and to understand their distinct characters. If the hand of charity was offered without individual involvement with the poor, there was the very real danger of aiding the slothful and unrepentant, who were reaping the just fruits of their spiritual rebellion. Cotton Mather warned his church in 1698, “Instead of exhorting you to augment your charity, I will rather utter an exhortation … that you may not abuse your charity by misapplying it.” Mather added, “Let us try to do good with as much application of mind as wicked men employ in doing evil.”[1] As a result of such teaching, there was a priority placed on categorization and discernment. Only those who were discerned to be poor through no fault of their own were categorized as “worthy of relief.” This category included orphans, the aged, and the incurably ill. The shiftless and intemperate who were unwilling to work were categorized as “Unworthy, Not Entitled to Relief.” Early poverty fighters who had grown up reading the Bible were keenly aware of the deviousness of the human heart. They were not surprised at all to find among the poor those who preferred their condition and even tried to take advantage of it. Only discernment on the part of charity workers who knew their aid-seekers individually could prevent fraud.

The family primary

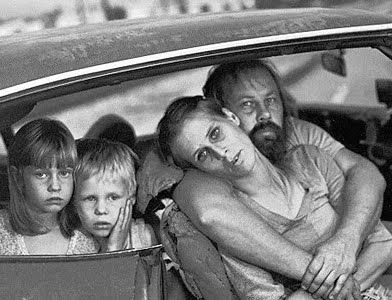

For early American poverty fighters, poverty was the problem of the local community, and particularly, the most local of communities—the family. There was strong emphasis placed on family relationships. Nothing that could contribute to the breakup of families or to the loss of the family’s central role as support of its members was encouraged. Early charity organizations instructed their volunteers to work hard at restoring broken family ties and strengthening a church or social bond. The prime goal of relief, all agreed, was not material distribution but affiliation—the re-absorption in ordinary social life of those who for some reason had snapped the threads that bound them to their families and communities. However, if the aid applicant was truly alone, there was an obligation placed on the charity worker to “bond” with the poor person—literally to incorporate the poor into his family. Just as the Good Samaritan went the extra mile with the man left for dead on the side of the road, so there was a priority placed on deep involvement with small groups of very needy poor individuals and families. The key was personal willingness to become deeply involved. This was charity according to its original meaning of ‘love,’ not charity in its debased meaning of ‘alms.’

For early American poverty fighters, poverty was the problem of the local community, and particularly, the most local of communities—the family. There was strong emphasis placed on family relationships. Nothing that could contribute to the breakup of families or to the loss of the family’s central role as support of its members was encouraged. Early charity organizations instructed their volunteers to work hard at restoring broken family ties and strengthening a church or social bond. The prime goal of relief, all agreed, was not material distribution but affiliation—the re-absorption in ordinary social life of those who for some reason had snapped the threads that bound them to their families and communities. However, if the aid applicant was truly alone, there was an obligation placed on the charity worker to “bond” with the poor person—literally to incorporate the poor into his family. Just as the Good Samaritan went the extra mile with the man left for dead on the side of the road, so there was a priority placed on deep involvement with small groups of very needy poor individuals and families. The key was personal willingness to become deeply involved. This was charity according to its original meaning of ‘love,’ not charity in its debased meaning of ‘alms.’

Religious beliefs put into practice

Affiliation, bonding, categorization, discernment, and a reliance upon the grace of God—these principles were the hallmark of early American poverty fighting. By the 1830s there was so much private charitable activity that American Christendom was said to be promoting a “Benevolent Empire,” the poor received Bibles, tracts, lessons at missions and Sunday schools, and material help when necessary and “rightful”. Social thought of this period did not insist on equal treatment for all that were in trouble. The goal, rather, was to serve individuals who had unavoidable problems. Religious beliefs underlay almost all activity. Literally scores of private charitable organizations served the poor, including The Female Charitable Society of Bedford, New York, the Massachusetts Charitable Fire Society, the Female Domestic Missionary Society for the Poor, the New Hampshire Missionary Society, the United Female Benevolent Society, the Female Charitable Association, St. Vincent de Paul, and the list goes on and on.[2] The Biblically orthodox Christians of the time worshipped a God who came to earth and showed in life and death the literal meaning of compassion—suffering together with. Christians believed that they—creatures made after God’s image—were called to suffer with also, in gratitude for the suffering done for them, and in obedience to biblical principles. They did not see God as a sugar daddy who merely felt sorry for people in distress. They saw God showing compassion while demanding change, and they tried to do the same.

The effect of the Enlightenment

But from the 1840s change was in the air. While barely perceptible to the general population, tectonic plates were adrift at the deepest levels of American culture and life. The ideas and values of the European “Enlightenment,” while present from the founding of the nation, increasingly challenged traditional Biblical orthodoxy. The centerpiece of Enlightenment philosophy was the confidence that everything in the world could be broken down into tiny cause‑and‑effect relationships, making all reality  nothing more than a huge machine—like a giant clock—of which the whole was no more than the sum of its parts. In classic Enlightenment thought, God was still retained as the creator, and a necessary “first cause,” but was increasingly, seen as uninvolved and distant from his creation. As the Enlightenment wore on, intellectuals claimed to have “come of age.” Enlightened people now had a sufficient understanding of the natural world and of the doings of humanity to get along without appeal to such outdated authority. In the church, the influence of the Enlightenment brought about a corrosive theological liberalism. Increasingly, mainline denominations emphasized the task of establishing the Kingdom of God on earth now merely through human efforts. Likewise, they began to overlook individual sin, underplay the need for repentance and salvation, and exalt the role of doing good works. The key agent in establishing the Kingdom of God was seen as the state. Only the state was large enough to address “structural inequality.” This school of thought would later become known as “Social Universalism.”

nothing more than a huge machine—like a giant clock—of which the whole was no more than the sum of its parts. In classic Enlightenment thought, God was still retained as the creator, and a necessary “first cause,” but was increasingly, seen as uninvolved and distant from his creation. As the Enlightenment wore on, intellectuals claimed to have “come of age.” Enlightened people now had a sufficient understanding of the natural world and of the doings of humanity to get along without appeal to such outdated authority. In the church, the influence of the Enlightenment brought about a corrosive theological liberalism. Increasingly, mainline denominations emphasized the task of establishing the Kingdom of God on earth now merely through human efforts. Likewise, they began to overlook individual sin, underplay the need for repentance and salvation, and exalt the role of doing good works. The key agent in establishing the Kingdom of God was seen as the state. Only the state was large enough to address “structural inequality.” This school of thought would later become known as “Social Universalism.”

Greeley, a Universalist, stirs the pot

The first popular challenge to the early American charity consensus came from the mid nineteenth-century’s leading American journalist, Horace Greeley. Greeley was the founder and editor of the New York Tribune, and was a Universalist. With characteristic Enlightenment optimism, Greeley believed that people were naturally good and that every person has a right to both eternal salvation and temporal prosperity. He advised young men and women to fight poverty by joining communes in which the natural goodness of humans, freed from competitive pressure and structural inequality, would inevitably emerge. While Greeley placed himself within the Christian tradition, he did not accept the prevalent religious thinking—that a man’s sinful nature leads toward indolence, and that an impoverished person given a dole without obligation is likely to descend into dependence. He saw no problem with supporting able-bodied poor who did not work.[3]

- Scott Allen

… to be continued

This paper was originally produced in December 2005.

[1] Robert H. Bremmer, American Philanthropy (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1960), p. 14.

[2] Olasky, pp. 16, 17.

[3] Horace Greeley, Hints Toward Reforms (New York: Harper & Bros., 1850), p. 86. Greeley agreed with statements by Unitarian leader William Ellery Channing citing “avarice” as “the chief obstacle to human progress… The only way to eliminate it was to establish a community of property.” Channing later moderated his communistic ideas concerning property, but he typified the liberal New Englander’s approach to the problem of evil. Evil was created by the way society was organized, not by anything innately evil in man.