In 1889, Jane Addams founded Hull House, a Chicago charity that prided itself in the absence of religious affiliation. This product of Social Universalism became the inspiration of governmental social work programs of the 1930s and community action programs of the 1960s.

The nation’s first major political attempt at a national welfare system came in January 1909, when two hundred prominent men and women met at the White House  Conference on the Care of Dependent Children and proposed programs to help the two classically needy groups, widows and impoverished children. First came proposals for what were called “widow’s pensions” and by 1919, widow’s pensions were available in thirty-nine states. Over the years coverage was extended to women whose husbands, for whatever reason, were unable to support their families. As the widow’s [now mother’s] pension movement blossomed, so did another outgrowth of the 1909 conference—the drive to establish a “federal children’s bureau.” This bureau quickly became a factory that churned out plans for extension of governmental involvement. The growing call for governmental action accompanied a new stress on professionalism in social work. As professionals began to dominate the realm of compassion, volunteers began to depart. Hired social work professionals, furthermore, became dependent upon government charity spending for their livelihood; thus they continued to emphasize the necessity of large-scale social and political change rather than personal involvement, which was increasingly seen as being old-fashioned.

Conference on the Care of Dependent Children and proposed programs to help the two classically needy groups, widows and impoverished children. First came proposals for what were called “widow’s pensions” and by 1919, widow’s pensions were available in thirty-nine states. Over the years coverage was extended to women whose husbands, for whatever reason, were unable to support their families. As the widow’s [now mother’s] pension movement blossomed, so did another outgrowth of the 1909 conference—the drive to establish a “federal children’s bureau.” This bureau quickly became a factory that churned out plans for extension of governmental involvement. The growing call for governmental action accompanied a new stress on professionalism in social work. As professionals began to dominate the realm of compassion, volunteers began to depart. Hired social work professionals, furthermore, became dependent upon government charity spending for their livelihood; thus they continued to emphasize the necessity of large-scale social and political change rather than personal involvement, which was increasingly seen as being old-fashioned.

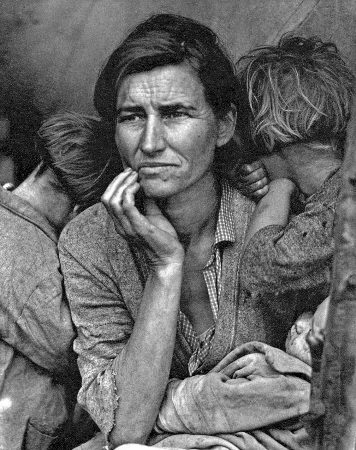

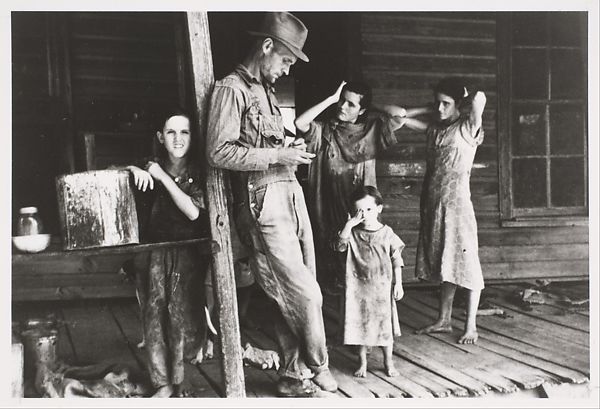

Effect of the Great Depression on charity through government intervention

The Great Depression of the 1930s only provided fuel to the government welfare fire. Frank Bruno wrote “Instead of being the Cinderella that must be satisfied with the leavings, social work was placed by the depression among the primary functions of government.”[1] The welfare revolution did not come spontaneously. In August 1931, the Rockefeller Foundation gave the American Association of Public Welfare Officials a grant of $40,000 for activities that included a program to “educate public opinion regarding the fundamental importance of welfare work in present-day government.”[2] Other groups also began proselytizing: The American Association of Social Workers (AASW) Committee on Federal Action on Unemployment concluded in April 1933 that “National Economic Objectives for Social Work”[3] should include social and economic planning through which all who desired it would be entitled to government support. Individual competition and incentives for personal gain would be curbed. For the AASW, poverty arose primarily out of “our faulty distribution of wealth.” Their primary spokesperson, Mary van Kleeck, dubbed the “high priestess” of social welfare, praised Soviet planning and presented papers that insisted on “A Planned Economy as a National Economic Objective for Social Work.” Her demand for a national income maintenance program (as part of a “collective, worker-controlled society”) was cheered. What was missing in all of this, of course, were the old Social Calvinist principles of affiliation, bonding, categorization, discernment, and the grace of God. Talk now was of the mass.

If poverty is the lack of money, the government can fix it: public charity

Replacing the old Judeo-Christian worldview as the predominate cultural influence in America, triumphant secularism provided a whole new ideological foundation for poverty fighting efforts. Because secularism is, by its very nature, a defiant rejection of any form or notion of spiritual or transcendent reality, poverty increasingly was seen as being materialistic in nature—and as a materialistic problem, it’s solution was well within the grasp of federal, state and local governments who held the power to tax citizens and redistribute wealth from the rich to the poor. As one Johnson administration official put it, “The way to eliminate poverty is to give the poor enough money so they won’t be poor anymore.”[4] Columnist Stewart Alsop wrote that for $12 to $15 billion a year (two percent of the gross national product at the time) “poverty could be abolished in the United States.” A 1964 Economic Report to the President, in the same vein declared boastfully that “the conquest of poverty is well within our power.”[5] Church groups might have been expected to counter such blatant materialism, but in fact, the mainline National Council of Churches became one of the leading sellers of entitlement. In a great reversal from church positions of the nineteenth century, council reverends argued though out the 1960s that not only did the poor have a right to handouts, but that the better-off should be ashamed if they did not provide them. While the mainline and liberal churches embraced the secular framework of Social Universalism, the orthodox, evangelical church fled from it. As a consequence of this retreat, nearly all its social activity and work with the poor was eliminated by the end of the 1930s. By the 1960s, the mainline Christian message was clear: poverty was socially caused and thus could be socially eliminated. Reflecting the new consensus, Lyndon Johnson declared his intention to create a war on poverty with full confidence in his ultimate victory.

A new definition of dignity: accept charity

During the infancy of federal welfare, the poor were often reluctant to accept government handouts, due to the social stigma, but through the 1950s and 60s, a steady war was waged on this latent sense of shame. By the 1960s, attitudes had changed. Suddenly, it became better to accept welfare money than to take work for small, minimally paying jobs. As Michael Harrington, author of the popular book The Other America wrote: “Until the 1960s, the public dole was humiliation, but thereafter, young men were  told that shining shoes was demeaning, and that accepting government welfare meant that a person ‘could at least keep his dignity.’”[6] This was a key watershed—not so much new benefit programs, but a change in consciousness, with government officials and professional social workers advocating not only larger payouts, but an all out war on shame. Along with this new consciousness came an explosion in welfare rolls. During the 1950s Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) rolls rose by 110,000 families, or 17 percent—but during the 1960s, the increase was 107 percent, or 800,000 families. By 1974, the AFCD roll was at 10.8 million.

told that shining shoes was demeaning, and that accepting government welfare meant that a person ‘could at least keep his dignity.’”[6] This was a key watershed—not so much new benefit programs, but a change in consciousness, with government officials and professional social workers advocating not only larger payouts, but an all out war on shame. Along with this new consciousness came an explosion in welfare rolls. During the 1950s Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) rolls rose by 110,000 families, or 17 percent—but during the 1960s, the increase was 107 percent, or 800,000 families. By 1974, the AFCD roll was at 10.8 million.

The virtual elimination of private and church-based charity

What were some of the consequences of this unprecedented explosion in government welfare programs? First, nearly all remnants of private and church-based charity were wiped out. Another big loser was marriage. As governmental obligations to single mothers increased, marital obligations held traditionally though out U.S. history decreased. As no-fault divorce laws spread, couples began to understand that unfaithfulness and divorce would mean suffering only a minor economic penalty. Federal government, in essence, replaced the mother’s husband. Overall cultural changes that glorified unrestrained sexuality, minimized the importance of marriage, and accepted single-parenting and easy divorce, were a tremendous blow to the poor. Individual giving was another casualty. Such giving, as a proportion of personal income dropped 13 percent between 1960 and 1976 as individuals came to expect the federal government to use their tax money to deal with the poor.

Compassion was reduced to pity

But perhaps the darkest legacy of the modern welfare experiment was the lost motivation, vision and dependency engendered among countless poor. Founded on a secular  and materialistic ideology, the welfare system harmed the poor by reducing them from human beings to digits—mouths to be fed. In all of this, the Judeo-Christian understanding of compassion—suffering together with—was somehow lost. It withered away in the incompatible soils of secularism. The idea of compassion—the idea of suffering together with—is a uniquely biblical concept. When the orthodox church abandoned its historical poverty-fighting role, it took with it the traditional definition of compassion. By the end of the 20th century, compassion had been reduced to a weak “feeling of pity,” the charity of government bureaucracy. While the old, biblical understanding of compassion carried with it a call for action and personal involvement in the lives of the poor, the modern understanding reduces compassion to an emotion—a discomfort that can easily be eliminated through the giving of a few dollars or a little free food.

and materialistic ideology, the welfare system harmed the poor by reducing them from human beings to digits—mouths to be fed. In all of this, the Judeo-Christian understanding of compassion—suffering together with—was somehow lost. It withered away in the incompatible soils of secularism. The idea of compassion—the idea of suffering together with—is a uniquely biblical concept. When the orthodox church abandoned its historical poverty-fighting role, it took with it the traditional definition of compassion. By the end of the 20th century, compassion had been reduced to a weak “feeling of pity,” the charity of government bureaucracy. While the old, biblical understanding of compassion carried with it a call for action and personal involvement in the lives of the poor, the modern understanding reduces compassion to an emotion—a discomfort that can easily be eliminated through the giving of a few dollars or a little free food.

The failure of the welfare system

The great American welfare experiment has failed. Throughout the 60s, 70s, 80s, and into the 90s, billions of dollars were spent on the war on poverty. The only concrete result was an entrenched government industry of bureaucrats, caseworkers, service providers, and a grab bag of vendors in the private sector that planned, implemented and evaluated social programs on government contracts. The actual number of poor in the U.S. in fact increased during these decades despite this massive reallocation of money. Today, all the talk is of welfare reform—reform not rooted in a return to the old principles and values of Christian poverty fighting, but simply rooted in a pragmatic sense that welfare is broken and we need to try something new. But the failure of welfare brings with it a tremendous opportunity for the orthodox church in America. The door is open for new ideas—and the church holds the answer—an answer rooted in the annuls of its own history and drawn from its own unique worldview. The question today is whether the church will recognize this opportunity or continue to isolate itself from society. The answer to this question will be decided in the individual minds of believers across the land.

- Scott Allen

This paper was originally produced in December 2005.

[1] Frank Bruno, Trends in Social Work, 1874-1856 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1948), p. 300.

[2] Josephine Chapin Brown, Public Relief 1929-1939 (New York: Octagon, 1971), P. 85.

[3] Jacob Fisher, The Response of Social Work to the Depression (Boston: G.K. Hall, 1980), p. 71.

[4] Quoted by Stewart Alsop, “After Vietnam – Abolish Poverty?” Saturday Evening Post, December 17, 1966, p. 12.

[5] “The Problem of Poverty in America,” Economic Report of the President (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1964), p. 60.

[6] Olasky, pp. 168, 169. See Organization Trends, March 1990, p. 2.

2 Comments

Jeanne Dalrymple

November 1, 2021 - 4:04 pmThank you for this series. Excellent and informative! It made me realize all the gaps I had in my history classes.

admin

November 8, 2021 - 4:44 amSo glad you enjoyed it, Jeanne! I know that many of us can relate to your experience. I hope you will share the series with anyone else you know that might be interested! May God’s Spirit grant us wisdom and success as we seek to bring about some needed changes in our society!